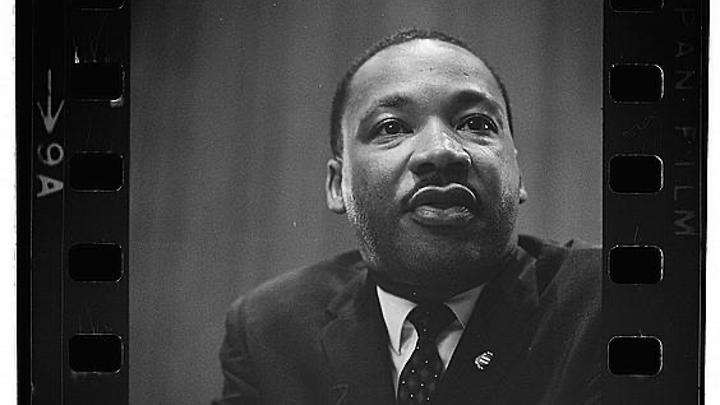

This weekend, we pause to remember the life and ministry of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. King offers powerful lessons for today, but those lessons grow more elusive as Americans – particularly white Americans – have gradually constructed a milder and gentler vision of him. Since his assassination, he has become almost universally admired in our nation as a model of courage and dignity. Not coincidentally, he is now seen as less disruptive to the status quo than he was in reality. We tend to focus on the Dr. King of 1964 rather than the Dr. King of 1966. I’ll explain what I mean.

I went to college in the South, and my roommate was from a small town in Louisiana. With the self-righteousness of an 18-year-old who had grown up in the “enlightened” North, I once started to lecture him about racial injustice in his state. He listened for a while, then he asked how many Black students were in my 1989 graduating class at my large public high school in Chicago’s suburbs. I was able to count my Black classmates on one hand, even though another large public high school 10 miles away had a predominantly Black student population. “So? That’s just the way it is. Now let’s get back to talking about racism in the South.”

My own obliviousness to the full legacy of American racism reflects the reality that also limited the long-term impact of King’s work. As with many areas of moral judgment, we’re much quicker to point fingers than we are to engage in deep soul-searching and corrective action. Indeed, when the critical gaze turns to us, we push back powerfully.

Witness the changing public reaction to King himself. From August 1964 to August 1966, Gallup surveys showed that the percentage of Americans who viewed King unfavorably jumped from 38% to 63%.

In the years leading up to 1964, King led the Montgomery bus boycott and spoke at the funerals of the girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing. He wrote his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, brought worldwide attention to Bull Connor’s regime attacking peaceful protestors with police dogs and fire hoses, and gave his “I Have a Dream” speech in which he envisioned a day when his children would one day be judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. And in that speech, he called out, in particular, the states of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi for their perpetuation of injustice.

So what happened between 1964 and 1966? King publicly opposed the Vietnam War for the first time, which could explain part of the shift in public opinion against him. I think the bigger change, though, was that King shifted his gaze to northern cities. He moved to Chicago and launched his first civil rights campaign outside the Deep South. Rather than target a southern society that advertised its segregation policies for all to see, he now protested deeply embedded real estate practices, such as steering and redlining, that kept Black families locked in northern ghettos. In 1965, he predicted, “If we can break the system in Chicago, it can be broken any place in the country.” He didn’t break the system, and I grew up in that system.

It’s easy to feel comfortable with King when he helps me feel morally righteous and confident in my place on the right side of history. I would never refuse service to someone based on the color of their skin. I would never turn the dogs loose on peaceful protesters. But when he starts asking what I’m doing about the inequality in my own community, I have to ask myself, “Am I less comfortable because it hits closer to home?”

So on this Martin Luther King Day, can I push through that discomfort and take action? In the hope that they might spur your own ideas, here are three concrete steps I’ll take this weekend: 1) Support Black-owned businesses (Support Black Owned Business Directory); 2) Spend a couple of hours learning more about Black history (10 Must-Watch Black History Documentaries on PBS); and 3) head to St. Peter Claver Church today at 11:30 a.m. to hear Yusef Mgeni share his history and experience of the Black Catholic community in the Twin Cities.

As we celebrate this holiday, I encourage you to take seriously Dr. King’s most powerfully persistent question: How will we use our gifts to help bind our nation’s wounds and build the beloved community?

University of St. Thomas President Rob Vischer sent this note to faculty and staff on Sunday, Jan. 15, 2023.