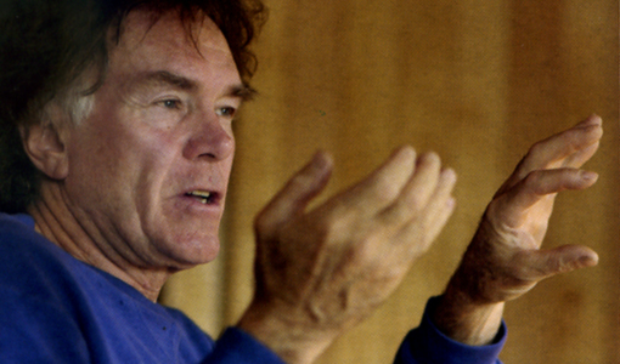

ELY – Will Steger kept a journal last year during his trip across the Canadian Barrens, scrawling his thoughts at night while huddled in his tent after a daylong trek in 40-below-zero weather.

A snapshot of Steger and his 85-year-old mother is affixed to the cover of the journal, and there is a quote from Irish poet William Butler Yeats:

The dreamers who must do what they dream,The doers who must dream what they do.

"I saw myself in that quote," said Steger. "I'm a doer. And I dream. I've always been a romantic, and I donÔt think I've lost that. I was fortunate to have parents who told my eight brothers and sisters and me to follow our dreams, and I have.

"I'm a dreamer and a doer who came up with ideas – and then did them."

As Steger talks about his dreams on this late-summer day, he sits in the cabin that he began to build four decades ago on Pickett's Lake northeast of Ely near the Boundary Waters Wilderness Canoe Area. It's a fine day, in the 70s, or more than 100 degrees warmer than the conditions he endured months earlier during his 2,000-mile, 155-day Arctic Transect expedition in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut Territory.

Steger is in a reflective and, one might conclude, celebratory mood. He will turn 60 the next day. He is marking his 40th summer since buying a plot of wilderness after his freshman year at St. Thomas. One of his biggest dreams – an environmental retreat center a few steps away – is getting closer to completion. He has finished another successful wilderness journey, which was followed by nearly 2 million students and teachers around the globe via the World Wide Web.

As he sips his tea, he looks back on four decades as an explorer, teacher, writer, photographer and lecturer – all filled with carrying out an intense passion to learn more about the far reaches of the world, to share that knowledge with everyone from elementary school youths to government leaders, and to do everything he can to protect the environment.

Steger ended up in Ely almost by happenstance. He took a 3,000-mile kayak trip through Canada in the summer of 1964 and, intrigued by cabins he saw, decided to look for property of his own. He found the right spot near Ely and paid $1,000 for 28 acres. He built his cabin during summers, later expanding it and buying more land in 1987 to accommodate other buildings and small cabins to support his expeditions. He owns 220 acres today.

He graduated from St. Thomas with a degree in geology and taught high school science while pursuing a master's degree in education, also at St. Thomas. He moved to Ely in 1970 and ran an outdoors school for 10 years before deciding to devote his full energies to exploration. He led dog-sled expeditions through Canada and Alaska before embarking in 1986 on the first confirmed dog-sled journey to the North Pole without resupply. Four years later, he led the first dog-sled traverse of Antarctica, a 3,500-mile journey.

Other trips ensued, including a 1,200-mile crossing of the Arctic Ocean from Russia to Canada in 1995, but in recent years Steger didn't have the same yearning for further exploration. He had tired of raising money for expeditions and decided to focus on close-to-home projects such as completing his retreat center. Then one day he had lunch with Dan Buettner '83, a fellow explorer and St. Thomas alumnus.

"I had been living a quiet, private life, not in the public eye at all," Steger said. "I was feeling politically isolated, and I had a growing concern about the state of the environment and the need for the United States to take more of a leadership role on issues such as global warming. Dan invited me to go on a biking and hiking expedition in the desert. That got me thinking. I started looking at maps of Canada, and the next day I knew I'd do the Arctic Transect."

Steger's primary goal was to learn more about the impact of environmental changes in remote Arctic communities. He designed an adventure-learning curriculum about traditional and contemporary life in those communities, and schools followed the trek online. He used satellite telephones to dictate his journals, which were put on the Web (www.polarhusky.com and www.willsteger.com).

The crew of six men and 31 dogs left Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, on Jan. 1, 2004, with just six hours of daylight, and headed across the Barrens, which Steger calls the coldest region in the northern hemisphere. "I chose a challenging route, with mountains and sea ice but not too much open water," he said. "It was below zero for three months, but we got used to that."

They traveled through Inuit communities, where they picked up supplies and spent up to a week in five of them to meet with elders and learn more about their culture and how they lived off the land. In turn, students following the expedition on the Web "learned more than just their ABCs," Steger said, "but increased their understanding and awareness of the environment.

"Global warming is a reality for the Inuit," he said. "They see major changes affecting their lifestyle, with earlier springs, warmer summers and later falls. They used to dry their meat and fish in the summer, but now it gets so warm that the meat rots. There also is the migration of southern species – animals, fish, even insects. Hunting patterns change. Sea ice isn't as thick."

The expedition concluded June 4 at Pond Inlet in Nunavut Territory, with 24-hour daylight conditions and temperatures in the 40s. Among Steger's appearances upon his return was in Washington, D.C., where he endorsed legislation to limit industrial carbon dioxide emissions and curb greenhouse gases that are believed to cause global warming.

Steger has seen climate changes in Ely, too, with warmer weather and higher carbon dioxide and methane levels in the atmosphere. He believes reasonable solutions exist but admits the politics of the situation can be discouraging.

"We have been made to believe what's good for the environment is bad for the economy, but that's not true," he said. "We have the technology to solve problems – to burn our fuels cleaner and to be more energy efficient – but there's not enough political will in the United States to take advantage of technology to improve the environment."

Steger hopes government and business will subsidize more alternative energy research and work more cooperatively with environmental activists and educators.

One avenue for that might be perhaps Steger's biggest dream – the retreat center for which he broke ground in 1988.

The unfinished center dominates the landscape on Steger's property, 58 feet high with five levels constructed out of recycled and native wood, stone and glass. At the top, you can walk around the outside of the structure and see nothing but miles of forest.

Steger always has envisioned the center as a 20-year project, and has a goal of completing it within four years. It will be a model of self-sustainability, he said, and will be powered by solar and wind energy, with a backup propane generator. He has financed its construction through his writing and lectures, and does the construction work himself and by tapping friends and groups such as the St. Thomas Geology Club or the Robbinsdale High School boys cross country team.

During a late-August visit, the runners spent two days on Steger's property, hauling dirt, digging ditches and taking long training runs in the morning and evening. "Most of these kids never have been off the power grid," said Steger, who got to know their coach through a friend. "A wilderness experience like this is inspiring and eye opening."

He hopes others will say the same thing once the center opens. He envisions it as a place where leaders "can get away from everyday surroundings, talk about ideas and build off each other's inspiration." The first group to use the center, for example, "could be environmental policymakers from the state laying out their vision for long-term energy use," he said. "The business community has to be involved, too, for this to be effective."

Earlier in the afternoon, as Steger walked through the center, he pointed frequently to areas where more work needed to be done. "It's never ending," he said at one point. When asked about the comment later, the dreamer and the doer who walked to the North Pole and the South Pole gently shook his head and talked about how he never has considered any challenge to be insurmountable.

"I always have had big dreams," he said. "But I don't see barriers, and if they are there I don't let them get in my way. I can overcome barriers because I believe in myself and I'm practical. I'll go over or under or around them."

That kind of attitude will drive the older and wiser Steger in the years ahead. In addition to finishing the center, he may undertake an expedition in 2006 on CanadaÔs Baffin Island, which he calls one of the prettiest places in the world. Other goals or ambitions?

"I want to live in the wilderness, be active every day outside, be close to nature, raise my own food and live as simple a life as I can," he said. "That's not a goal, though. It's a journey."

Will Steger and St. Thomas

• Received three gradute degrees — a bachelor of arts in geology (1966), a master of arts in education (1969) and a honorary Doctor of Letters (1991).

• Named Distinguished Alumnus in 1990. His parents accepted the honor on his behalf on St. Thomas Day because Steger had just finished his seven-month expedition across America.

• Founded the World School for Adventure Learning at St. Thomas in 1993. It provided adventure-based curricula for elementary and secondary schools until closing in 1997.