Tucked away in a corner of the O’Shaughnessy Science Hall on the St. Paul campus, you’ll find the geology lab. Under the microscope today is a special sample that could hold important clues to the ancient Roman world.

Lab manager Anik Regan is working with Sophia Ritacco, a sociology major and art history museum studies minor. Together, they’re carefully analyzing a series of wall painting fragments collected by St. Thomas students from an ancient Roman villa in Croatia. What they discover could give archeologists and art lovers all over the world a better understanding of those who came before us.

Since 2008, more than 50 University of St. Thomas students like Ritacco ’23 have embraced the journey to St. Clement, a tiny island off the coast of Croatia. Once they finally arrive – the journey includes at least two long-haul international flights and multiple boat rides – they begin digging into a marquee experience at the heart of the university’s collaborative research.

“When we got off the boat, grabbing all of our luggage, everyone was super excited to be done traveling,” Ritacco, a University of St. Thomas senior, said. “And we immediately just went for the water and the beach. The sun was setting, and we knew the next day the digging would begin.”

Each summer the students excavate a small trench or two, offering a window into the ancient Roman estate that once played a crucial role in island life.

The bustling villa was at its prime more than 1,000 years ago, with a booming business in the trades of salt, fish sauce, wine and olive oil. Evidence discovered by St. Thomas scholars suggests that the estate was overseen by an elite owner and that its interior was stylishly decorated.

That ancient interior decorating is of particular interest to art lover Ritacco, who has focused her research on fragments of a long-forgotten wall painting. And while she admits that the experience on-site was life-changing, Ritacco’s archeological journey was far from over.

“Being on the island was an amazing field experience for me – you learn so much about the area, the history, and about the actual process of digging and doing archaeology,” Ritacco said. “But what was really interesting was coming back and studying those painting fragments in the lab.”

Studying ancient art history on campus

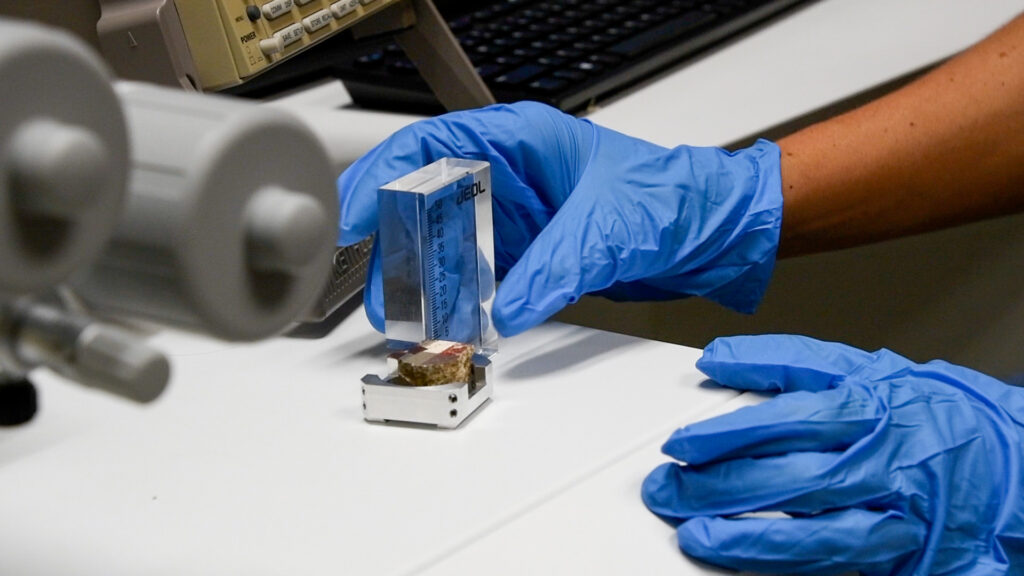

Once all the dusting, cleaning and cataloguing on-site was complete, the team was allowed to bring small samples of the wall painting back to St. Thomas for further study. Ritacco has enjoyed spending hours upon hours taking a deep dive into the ancient Roman pigments.

“Finding the composition or the elements used in the pigment could tell us whether resources were sourced on the island or maybe even contributed in trade routes through that area,” Ritacco said.

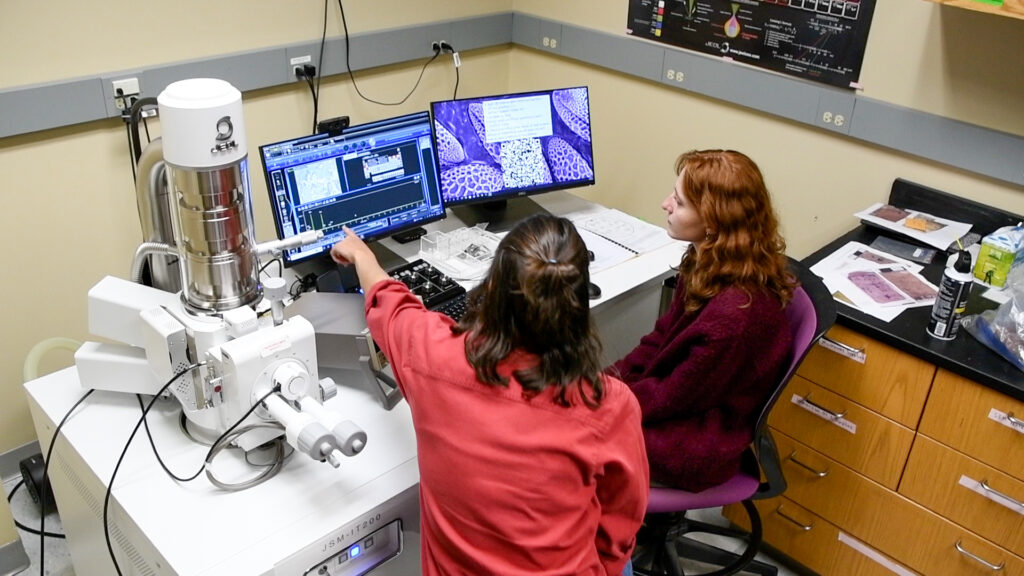

But to truly learn all that could be had from these painted fragments, Ritacco knew she’d need help outside her own area of expertise. She quickly turned to her friends in the Geology Program. Under their guidance, Ritacco has put the painting fragments under the microscope – some very fancy microscopes.

Using microphotography, Ritacco has been able to identify individual brushstrokes and cracks in the surface of the fragments. And in the geology lab, she’s used a scanning electron microscope, which identifies the topography and composition of fragment pieces.

“I don’t know a lot about science or chemistry, but it was a great experience discovering everything that goes along with archaeology,” Ritacco said. “I was able to dig in with this interdisciplinary work, with everything coming together back at St. Thomas.”

Art history professor Vanessa Rousseau has advised Ritacco each step of the way and worked to encourage that sense of collaboration, whether on-site or back at the geology lab.

“This is a perfect example of why the liberal arts are important, because it is a collaborative space where people with different expertise can come together,” Rousseau said. “It’s also a really good model for students to see that no one professor knows everything or pretends to know everything. We all have to ask each other questions and learn from one another.”

The Croatia excavation project has featured interdisciplinary research since its inception. Some years you’ll find students with majors in history and biology, other years engineering and geography, or geology and museum studies. Previous students have brought together their specialties to study ancient and modern water management, Roman winemaking, and the effect of sea level changes on ancient structures.

The origin story

Through it all, there has been one constant – the woman who has made this all possible – Ivančica (Vanča) Schrunk. Senior adjunct faculty in the Department of History, Schrunk grew up in Croatia. With a tip from a colleague back in her native homeland, Schrunk discovered the St. Clement archeological site, which hadn’t been touched by archeologists since the 1950s. Without hesitation, Schrunk started gathering support and funds, earning a grant from St. Thomas in 2009 to help bring students to the island.

“It was a fantastic site, and had great opportunity to do collaborative research,” Schrunk said. “Right away, I went to the office of grants and research at St. Thomas and said, ‘I have this shovel-ready project that I would like to take students on.’”

Schrunk’s idea to embrace collaboration at the dig site started from the very beginning. She knew the land around the site would need to be surveyed, so she invited members of the Geography Department. Invitations to the Biology, Geology and Art History departments would quickly follow.

“The project is ideal for connecting many different students and introducing them into worlds that they are not familiar with,” Schrunk said. “And it certainly benefits them as they graduate and look for employment if they get wider opportunities to learn.”

The St. Thomas team also works in cooperation with Croatian researchers, which gives them access to the site. In the past, Croatian students from the University of Zagreb have even joined them in their research.

A STEAM collaboration

The spirit of interdisciplinary collaboration is behind a massive new investment in STEAM education at St. Thomas. In 2024, the multimillion-dollar Schoenecker Center complex will open on south campus, creating a new flagship home for STEAM learning at the university.

Professor Kevin Theissen, geology program director, has watched the center’s construction progress from his office. After joining the Croatia excavation team this past summer, he’s excited to continue that legacy of innovation between departments.

“At first blush you might be like, well, what do we have to offer to each other?” Theissen said. “But they’re there, right? And a project like this really shines a light on that."

Theissen brought two of his students majoring in geology with him to the dig site. Together, they worked to collect core samples from the bay adjacent to the ruins. Their goal was to reconstruct past environmental conditions to see what human influences have been left on the landscape.

“There are these commonalities that can come across in work like this,” Theissen said. “A lot more is going to come from STEAM, and having arts and sciences and engineering disciplines in close proximity with each other is such a good thing.”

A lover of research by drone, St. Thomas alumna Emma Steffenhagen was recruited by Professor Schrunk to join the group’s 2018 trip to the island. Steffenhagen, who received her bachelor’s degree in 2019 as a geography and environmental studies double major, split her time between digging and mapping the excavation process by drone.

“The most gratifying thing of the whole experience was to see that I could do something useful in this wild and beautiful place, to record something that could hopefully be valuable for Professor Schrunk and our excavation team,” Steffenhagen said.

Professor Schrunk estimates that at their current speed it could take another 100 years to fully excavate the Roman villa. And that’s not a bad thing. In fact, she’s excited – excited to continue reaching across hallways at St. Thomas, widening what’s possible for decades to come.

“These connections put our students in a great position,” Schrunk said. “And for archaeologists, what we’re able to do together on this island, it widens our knowledge, deepens our knowledge. I hope we’re able to do this work long after I’m gone.”

The 2022 Croatia excavation research project was made possible, in part, by a grant from The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.