Storm Lake, Iowa – April 10 started out like any other Monday for Art Cullen.

He sat in the newsroom of The Storm Lake Times, of which he is editor and co-owner in his northwestern Iowa hometown, and planned the Wednesday edition. His brother John, publisher and co-owner, was at the next desk. Wife Dolores, a feature writer and photographer, and son Tom, a reporter, were steps away. Mabel the news hound snoozed on the floor.

At 2 p.m., Cullen secretly began to monitor the livestream announcement of the 2017 Pulitzer Prizes. He had submitted a 10-editorial entry and while he felt it was strong, he tried not to get his hopes too high. He had entered the contest before and not won. The odds of a twice-a-week, 3,000-circulation newspaper beating the likes of The New York Times to win the most prestigious award in American journalism seemed far-fetched.

“But I still felt I was going to win,” he said, having prayed to St. John Bosco, patron saint of editors, for good luck. “I just knew I had a winner. There were 21 categories, and editorial writing was No. 18 to be announced. My heart was just about coming out of my chest. But the closer we got, the more confident I was.”

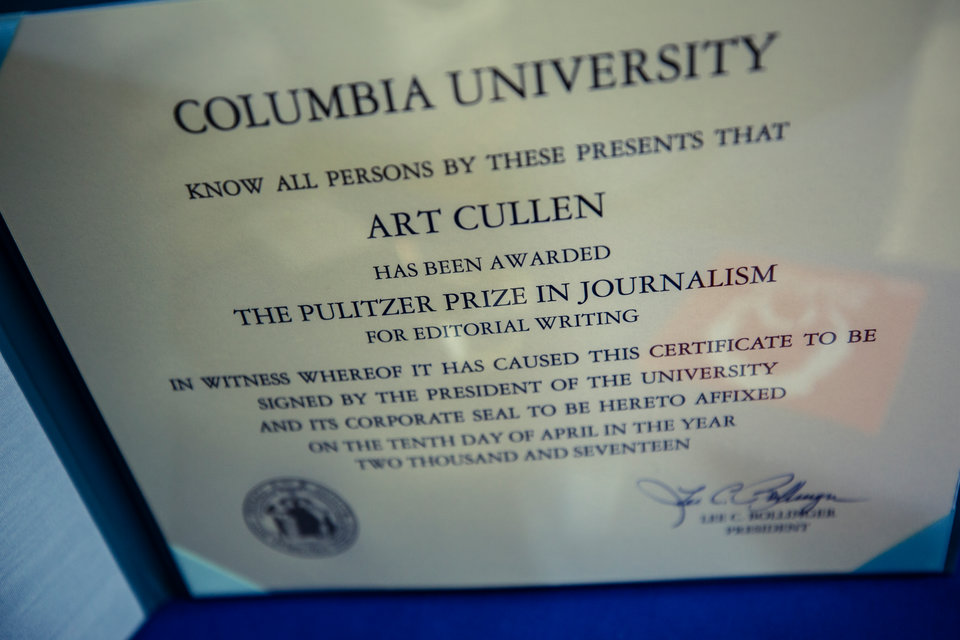

And then the announcement came: Gerald Arthur Cullen had won a Pulitzer Prize “for editorials fueled by tenacious reporting, impressive expertise and engaging writing that successfully challenged powerful corporate agricultural interests in Iowa.”

The 1980 St. Thomas journalism alumnus exploded. “We won! We won!” he shouted.

His brother gave him a blank stare and asked, “What did we win?”

“The Pulitzer!”

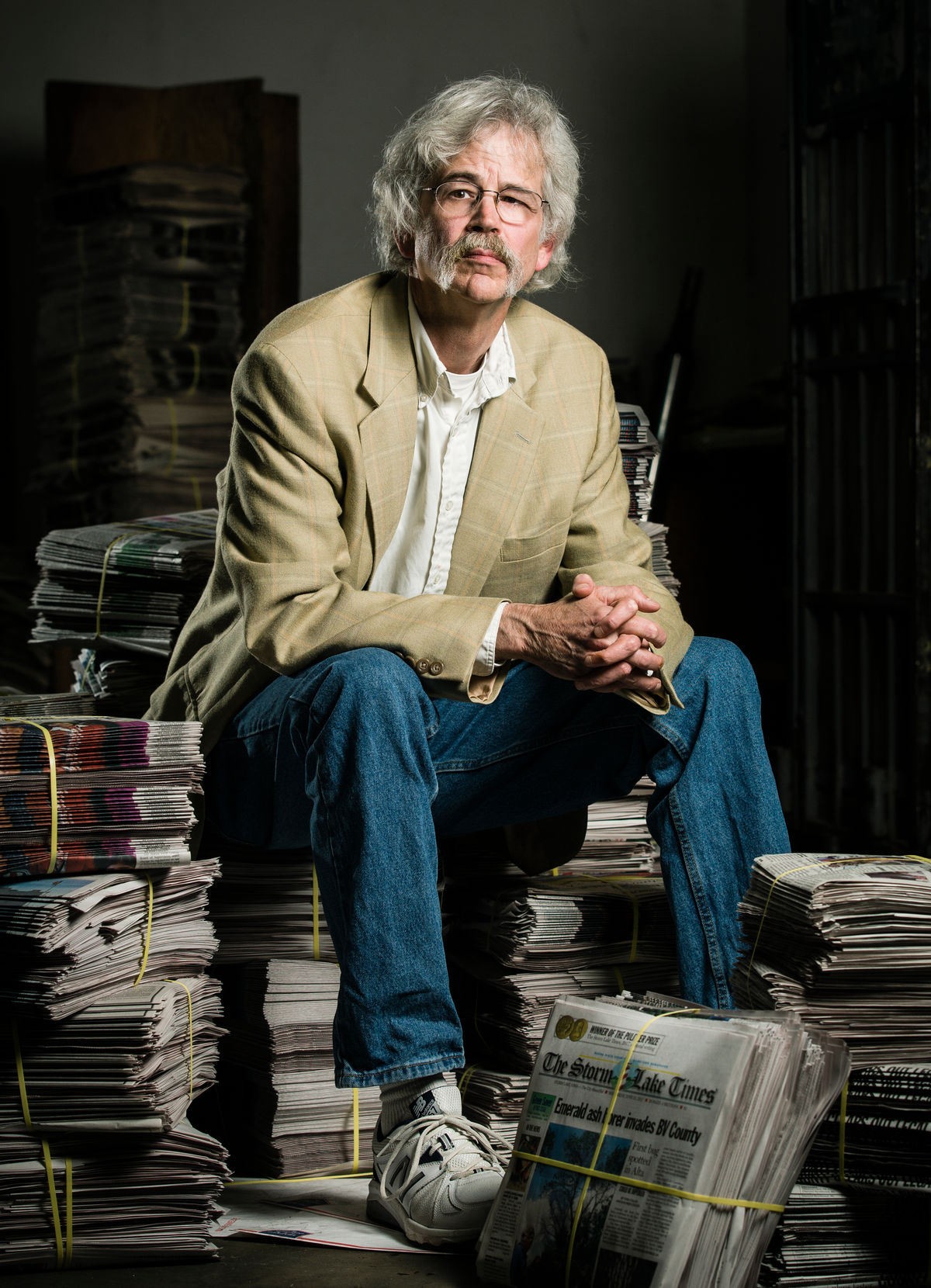

The editor, who resembles Mark Twain, jumped to his feet and hugged his brother. His wife snapped a photo outside of father, son and brother in front of the words “The Times,” which jump off the building in big blue type on what Cullen calls “Storm Lake’s First-Amendment Machine Shed.”

Then they went inside to drink champagne with well-wishers and plan a new Page 1A. “The Times Wins the 2017 Pulitzer Prize” the headline blared. A sub-headline read: “Buena Vista County’s hometown newspaper beats Washington Post, Houston Chronicle.”

It was quite the heady experience, and more was to come. Journalists from Japan, Australia, Ireland and across the United States called Cullen or descended on Storm Lake, population 11,000.He accepted a book deal with Viking Press. He flew to Washington, D.C., to address the National Press Club and to New York to receive the Pulitzer gold medal and a $15,000 prize.

Vindication

The Pulitzer has brought exhilaration to Cullen and the Times, but he chooses a different word to describe what it means.

“Vindication,” he said, referring to the Times’ three-year investigation of a Des Moines Water Works lawsuit against drainage districts in Buena Vista, Sac and Calhoun counties. The lawsuit alleged that excessive nitrate concentrations caused by agricultural runoff polluted the Raccoon River, a source of drinking water for 500,000 residents of central Iowa.

Cullen's Pulitzer Prize certificate is on display in the Storm Lake Times newsroom.

The river’s source is northwest of Storm Lake and it meanders 150 miles southeast to Des Moines.

Standing on a bridge over the Raccoon, Cullen points to land on both sides of the road. One side has a grass buffer greater than 30 feet between corn and the river, but on the other side corn is planted within a few feet of a slope to the river. Narrow buffer strips, he insists, are ineffective in halting erosion and runoff exacerbated by drainage tile.

“We didn’t have a nitrate problem before Earl Butz told farmers to plant row to row,” Cullen said of the former U.S. agriculture secretary. “If you left 10 percent to grass today, you would eliminate 90 percent of free-flowing nitrates. But it’s very difficult to change habits prescribed by the agriculture supply chain.”

Cullen also suggests farmers rotate crops regularly and take advantage of the Conservation Reserve Program, which pays for fields to remain fallow, but they “roll the dice” because of the prospect of earning more money by planting corn.

In 2013, Cullen attended an Iowa Environmental Council meeting and picked up a tip: the Des Moines Water Works would sue Buena Vista County because of nitrate pollution in the Raccoon. He returned to Storm Lake and published a Page 1A story with “two decks and a 96-point headline!” As the Times increased news coverage and editorials on the issue, it encountered some backlash in a community dependent on agriculture.

“All we did was inform the public who was pulling the strings – that there was dark money involved and who was behind the money,” Cullen said. “That was our job.”

The Times urged a settlement, but the litigation dragged on and the counties engaged law firms in Washington and Des Moines. Their legal fees totaled $1.1 million, paid by anonymous donations made to the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. The Times, working with the Iowa Freedom of Information Council, demanded the donors’ identities but the association would not comply.

A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit last March. In his editorials, Cullen blasted the county board for meeting in closed sessions after the lawsuit was dismissed, ostensibly to determine how to pay attorney fees.

“We said the lawsuit has been dismissed – there is no litigation to discuss behind closed doors,” he said. “How can you meet in closed sessions? They said our claim was fake news. When they finally opened the meetings, they refused to discuss the issue.”

The Cullens wrote dozens of stories (by Tom) and editorials (by Art), and he quietly submitted the Pulitzer competition entry. In winning, Cullen followed the footsteps of a mentor and former boss, Michael Gartner, who won a Pulitzer in 1997 for editorials in the Ames (Iowa) Tribune.

Cullen near the Raccoon River outside Storm Lake.

“Art is a natural,” Gartner said, who called Cullen to say he was happier for his protégé than when he won his Pulitzer 20 years ago. “His strength is in his editorial writing, where he combines his writing and reporting skills with his sense of outrage. He’s effective because he has the facts and knows how to marshal them to make his point.”

Gartner admires all of the Cullens, who publish a newspaper “for love and out of a sense of great purpose. ... They’re not getting rich.”

A budding journalist

Art Cullen didn’t plan to be a journalist.

The youngest of six children, he wanted to go to the University of Iowa in 1975. His mom refused, saying, “You’re going to St. Thomas!” A St. Catherine graduate, she wanted one child to enroll at St. Thomas or St. Catherine, but the first five went to other Catholic colleges. St. Thomas was Art’s only option.

So he settled into fourth floor Ireland Hall and referred to himself and his party-loving buddies as “rebels without a cause.”

He intended to major in music “but I was told, ‘No, you can’t play the piano.’ I looked at theater and realized I had to read huge tomes of Shakespeare. I was going to major in business but I flunked accounting. I had a 1.8 GPA and I’m sure I was on probation. I looked at the catalog and thought journalism would be a good major – the only requirement was to type 25 words a minute,” he joked.

It took five years to earn a degree, and he credited several professors. He said his best course was Persuasion in Writing taught by Father James Whalen, because “I had been mounting arguments all my life, and I was interested in the foundation of rhetoric.” He also favored the required philosophy classes of logic (Dr. Harry Austin) and ethics (Dr. Fred Flynn), and found his best professor in Dr. Lon Otto. “Lon taught me how to write. I took a creative writing class from him and it opened the world.”

Cullen made $1.80 an hour as a copy boy at the Minneapolis Tribune during school. He landed an internship in 1979 in Algona, Iowa, where his brother edited the Algona Upper Des Moines and Kossuth County Advance. His first stories filled a 96-page section on the town’s 125th anniversary, and after the section was printed he celebrated.

“I heard sirens and asked a neighbor what was going on,” he said. “A tornado had just torn up half the town. I ran back to work and we put out a 20-page, ad-free section. I had been interviewing old people and writing history stories all summer, and then the tornado hit. It was real news.”

Once he became a journalist, Cullen changed his byline. Known as “Jerry” in college, he switched to his middle name. “It was a better byline,” he said. “Jerry” reminded him of comedian Jerry Lewis and “Art” brought memories of columnist Art Buchwald.

Cullen stayed in Algona for seven years and succeeded his brother as editor. He wrote extensively about the farm crisis in the 1980s, winning a national award and $10,000, but he found the situation depressing. “You could see the county imploding,” he said. “The motto in Algona became, ‘Will the last person to leave town turn off the lights?’”

He left Algona to become managing editor of the Ames Tribune under Gartner, and spent a year at the Mason City Globe Gazette as night managing editor. His brother called in 1990 to say he was starting a weekly newspaper (the Times) in their hometown, even though it already had a paper (Pilot Tribune). He wanted Art to join him, but Art said no. He still hoped to write for the Minneapolis or Des Moines newspapers; when his brother called a second time, he agreed.

“It was terrifying,” Cullen said of the newspaper war between the Times and Pilot Tribune, “but I was full of myself and got into the nitty gritty of it.” The Times switched to daily publication in an attempt to gain an edge but lost money, so after 10 months John decided to cut back to twice a week. “He was born with horse sense,” Cullen said, “and I with the ability to BS.”

Community advocates

From the outset, the Times wanted to make a difference in Storm Lake.

“We always have felt a responsibility to be a mirror of the community,” John said, “so we report what happens, good or bad. Some media are reluctant to do that because they don’t want to alienate readers or advertisers. We always publish the truth, and let the chips fall where they may. If you don’t have your integrity, you don’t have anything.”

Mabel the news hound takes a break on the floor of the Storm Lake Times news room.

In addition to “chicken dinner news and the cover photo of the little girl who found a four-leaf clover,” John insisted on a strong editorial page. Art writes editorials and a weekly column – “I have not missed one in 27 years” – and his brother calls him “fearless. I give him free reign, and I can’t recall ever telling him not to run a story or an editorial. He knows what he’s doing.”

A bond referendum for a new middle school had failed twice but succeeded the third time thanks to the Times’ advocacy, and voters also approved a referendum for a new elementary school. Cullen has been an outspoken supporter of the rights of immigrants – 80 percent of Storm Lake elementary students are children of color – who hold jobs at large-city employers such as the Tyson meat plants.

A decade ago, the Times pushed for Project Awaysis to redevelop the north shore of Storm Lake and to build King’s Pointe, a water park resort.

“There wasn’t a place to eat or sleep on the lake,” Cullen said. “We had a tremendous asset being underused, so we said, ‘Let’s diversify our economy and become a tourist community.’”

Storm Lake sought state funds from a Vision Iowa initiative chaired by Gartner, and Cullen turned to his former boss from Ames.

“I called him and said, ‘We need $10 million.’ He said, ‘Will $8 million do?’ and I said yes. I wrote a story, before the announcement, saying we would get $8 million. The city didn’t know Gartner and I had talked and [it] went nuts. The mayor said, ‘You’re going to blow this for us. Where did you get that information?’ They were so mad at me. I told them, ‘Don’t worry. The money is coming.’”

And it did. The grant leveraged private donations and voters approved a sales tax to pay off bonds. King’s Pointe evolved into a $40 million project that includes a hotel, indoor and outdoor water parks, and a nine-hole golf course. The project tied into a Times-led effort to use tens of millions of dollars in federal, state and local funds to dredge Storm Lake.

“No other newspaper in Iowa has agitated on behalf of a lake for 25 years,” Cullen said. “The lake was a dumping ground, and now we’re taking care of it. I don’t know of many communities with a self-directed watershed management program.”

The editor

Back in the newsroom, the editor who has been called a “prairie populist” and a “tree-hugging lunatic” stretches his legs while sitting in a chair stained by ink from when he ran the Times’ printing press; he would go from the press room to his desk without changing his pants.

He is dressed casually – slacks, wrinkled shirt, blazer and tennis shoes – “and fits a preconceived notion of editors with the disheveled hair and droopy mustache,” Gartner said. Cullen’s wife of 32 years appreciates how “he has cultivated the rumpled editor look” but likes to remind him, “That’s one step from looking homeless.”

She credits his curiosity for getting him in – and out of – trouble. “He immediately tries to figure out the most important thing in a story,” Dolores said. “He always asks, ‘Why is this interesting? Why should people care?’”

Tom Cullen describes his dad as “a real bulldog” during the lawsuit. He remembers growing up with a man with a reputation as a “divisive” figure. “Kids would give me a bad time and I’d come home and talk to him. I’d say, ‘So and so says you’re wrong’ and he’d say, ‘Good. That means people are reading.’”

Art surveys a room with walls full of framed newspapers, award plaques, a Times billboard for visitors to sign and Pulitzer mementos. A letter from Brian O’Brien, consul general of Ireland in Chicago, promises a visit: “You make Ireland proud! Comhghairdeas” (Gaelic for congratulations).

Alas, what promised to be a quiet summer was anything but. In addition to editing the Times and dealing with post-Pulitzer hoopla, he has that book to write. He says it will be about life changing in rural Iowa and “the people who remain here – hard-working, productive, smart people who care.”

People like Gerald Arthur Cullen.

Art Cullen is the second St. Thomas journalism alumnus to win a Pulitzer Prize in five years.

Jeremy Olson '95 and two Minneapolis Star Tribune colleagues won a Pulitzer in 2013 for a series of stories on the increase in infant deaths at poorly regulated in-home daycare centers. The stories resulted in legislative action to strengthen rules, and deaths dropped dramatically.

Read more from St. Thomas magazine.