When Victoria Young first saw Saint John’s Abbey Church in Collegeville, Minn., she did not care much about it. She was a kid who was really excited to drop her sister off at the university for a week of camp.

As an art historian who studies architecture, Young later became more interested in the abbey church’s architectural story. Since then, Young has attended funerals, Masses and other services at which she has seen the unadorned, concrete building come to life when the sounds of monks chanting or congregants singing fill the space.

“I really became more interested in the purpose of the building more than the technology, engineering or materials or things like that. And that’s not good or bad, but it was just a focal change for me,” Young said. “Now I think of (the abbey church) differently, because I don’t think you can get the full impact of that building unless you attend a service.”

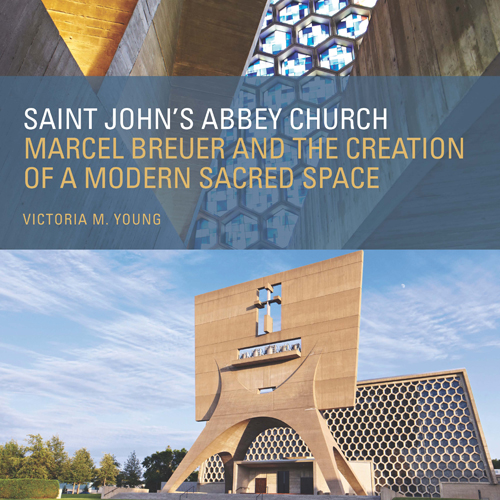

The purpose of the building is the focus of Young’s book Saint John’s Abbey Church: Marcel Breuer and the Creation of a Modern Sacred Space.

The book has attracted several accolades far from Minnesota and been dubbed by critic Norman Weinstein, writing for ArchNewsNow, as “The first great architectural history of the 21st century.” It was also named one of the top 12 architecture books of 2014 by the influential magazine Architectural Record.

Victoria Young

Published by the University of Minnesota Press, the book documents the story of the abbey and explains its role as a game changer in liturgical reform. Construction on the abbey church began in the late 1950s, when the Benedictine monks at Saint John’s were pushing for the church to encourage more engagement with its congregation. Thus, the building’s design is a manifestation of a period of transformation in the Catholic church.

“I really understand now how the space upholds the liturgical reform notions that were happening at the time,” Young said.

The monks had a clear vision for the space and sought top architects from around the world. Marcel Breuer ended up winning the contract to build his first sacred space and a cluster of buildings that still sit on the campus of Saint John’s University, including the library.

As Young studied the abbey church’s creation, what she unearthed were lessons in sacred space as the Benedictines actively educated Breuer. The two parties exchanged information, including essays the Benedictines wrote on topics such as the orientation of a church and the significance of its altar. They gave Breuer books and sent him to the Abbey of Maria Laach in Glees, Germany, where he came home with documents and guidebooks. Breuer listened and collaborated. Young said she came across a piece of paper in the archives on which a monk had written a note about Breuer’s first visit to Collegeville: “He didn’t say anything until the end of the day.”

As Young studied the abbey church’s creation, what she unearthed were lessons in sacred space as the Benedictines actively educated Breuer. The two parties exchanged information, including essays the Benedictines wrote on topics such as the orientation of a church and the significance of its altar. They gave Breuer books and sent him to the Abbey of Maria Laach in Glees, Germany, where he came home with documents and guidebooks. Breuer listened and collaborated. Young said she came across a piece of paper in the archives on which a monk had written a note about Breuer’s first visit to Collegeville: “He didn’t say anything until the end of the day.”

She found a letter of recommendation written by Abbot Baldwin Dworschak to assist Breuer in adopting a daughter, and she considered it strong evidence of the mutual respect the parties developed in the process of collaborating on the abbey church.

The respectful dialogue and collaboration between Breuer and the Benedictines are exactly what Young teaches her students when they study a building, especially in the context of sacred space.

“You can get so many things - religion, people, architecture and context - by looking at one building,” Young said. “You can use one building to allow you to look at it from multiple vantage points, so that becomes very important for my kids.”

In the first day of her American architecture class, Young shows students a picture of a building. She asks, “What are the questions?” and the students spend up to half an hour writing every question that comes to mind about the building. The questions get down to the smallest details, such as why did they pick white for the inside wood panels?

Young types up the list of those questions and prints them for the students.

“So I keep telling my students all semester long, remember the list of questions we made on the first day? Ask them every time,” she said.

But Young said the study of a sacred space opens further questions to a deeper spiritual level, because these places are designed with the divine in mind. The intentional design and function of the space are more connected.

Young said studying sacred space becomes more interesting at St. Thomas, where about half of the students are Catholic and about 90 percent have a religious affiliation. St. Thomas students respectfully engage and listen to different spiritual viewpoints, Young said.

“We can talk about a synagogue just as easily as a church or mosque or Disneyland as a sacred space because of the respect that goes on, and that to me is just the most gratifying thing I can see,” she said. “All these people of different religious persuasions want to understand buildings of every faith and then see the commonalities that exist because there are so many.”

Not everyone will see Disneyland as a sacred space, Young said, but they can agree it is a place of pilgrimage with a structure of respect.

The ability to have these respectful discussions considering different viewpoints fits into the university’s mission, and it is a foundational outcome of a St. Thomas education, Young said.

“If you can’t convince students of that now, it doesn’t bode well for the future,” she said.

Interior of the Abbey Church

Young said her book has opened dialogue about sacred space in other venues, too. A number of people who were part of the project are still living. Young enjoys discussing the abbey church with them, even with the healthy Tommie-Johnnie rivalry that arises frequently in conversations about a St. Thomas professor studying a Saint John’s church.

“Books should never close the deal; they should be opening the deal. They should be presenting information to people, so they want to know more, do more, think more about this,” she said.

Young said she has been overwhelmed by and grateful for the reception of her book after its October 2014 launch at an event hosted by Saint John’s. She was interviewed by several major news outlets in the Twin Cities, including MPR and TPT’s Almanac, and invited to lead public discussions in Pittsburgh, in Washington, D.C., at the University of Virginia where she did her graduate and Ph.D. work, and at New York University, where she studied as an undergraduate.

“A lot of people told me a monograph on a single building was the kiss of death in my field, but I never thought it was,” she said. “A lot of people told me that, but thankfully my publisher didn’t believe it.”

Young is currently working on an architectural monograph about the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, designed by Voorsanger Architects PC of New York.

Her students study both the spaces, and Young said she continues to learn from these in-class conversations about architecture.

“I remember an atheist saying something that was the most insightful thing I had heard about a sacred space ever. This is a guy who isn’t even spiritual. But those moments exist here because that’s the culture that exists at St. Thomas,” she said. “We are in this Catholic school with a mission to create moral and ethical responsibility, as well as respect for other people’s traditions. That moves into the classroom so well.”

“Bringing your ideas to bear at the classroom discussion level takes us as historians to places I’ll never get to in a book ever – because you’ve got 10 people sitting around you with their own really insightful thoughts on the built environment,” Young said. “That’s the beauty of St. Thomas.”

Read more from CAS Spotlight.