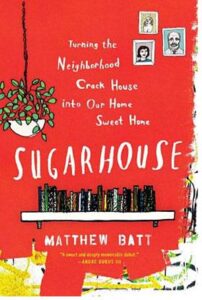

The English Department invites the public to a free reading celebrating the recent publications by two of its faculty members Friday, Sept. 21. Dr. Matthew Batt, author of Sugarhouse (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), his debut book, and Dr. Leslie Adrienne Miller, author of Y (Graywolf Press), her sixth poetry collection, will read from 7:30 to 9 p.m in the John R. Roach Center for the Liberal Arts auditorium (Room 126).

With a nonfiction writer and poet filling the space of an evening, the event promises to be eclectic and entertaining. Batt's memoir chronicles his and his wife's three-year saga renovating a former crack house in Salt Lake City. The pair, who had no prior construction experience, undertook the project amidst a series of personal turmoils that put their marriage to the test. In the end, they successfully transformed a house, and their relationship, for the better. The poems in Y, Miller says, "aim to enlarge the kinds of questions we ask about childhood and its role in the broader human culture." Former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser called her work as a poet "delightfully eclectic, learned and wise."

Both writers/professors took some time out of their busy schedules the first week of fall semester to answer a few questions about their perspectives on writing and reading. If you want to learn more about Sugarhouse and Y, you'll have to hear it straight from the sources this Friday.

Tell us about your first book reading in which you were the "star."

Batt: Sugarhouse is my first book and it's only been out for a couple of months so I remember pretty well every reading I've done. There have been some really nicely attended ones and then, well, some were, shall we say, very intimate. But I abide by the rule of thumb where any literary event is a success if the audience outnumbers the reader. I have been the only attendee of events before. I'm sure at some point I'll be that reader, too. As for numbers and such, I guess I've done a dozen or so readings – lots of radio and some local-ish TV stuff. And I absolutely always think I'm going to be super nervous, and then, for no reason I can figure, I end up being mostly OK. But what do I know? Ask the audience!

Y by Dr. Leslie Adrienne Miller, English Department.

Miller: I don't remember the first time I read from a book I'd written, but I do remember the first time I read published poems to a live audience. I had the good fortune to have some poems published in my college literary magazine, and the publication reading on our college campus was a big event each spring. Certainly, I was nervous about it, but the excitement and pleasures of joining a community of writers and readers around me made it an invigorating experience, and I think that's largely still true when I give readings now. I still get nervous, but I know that once I get going, I'm inside the work, and if the audience is a good one, they will go there with me.

What kind of work are you most drawn to reading? Do you find that you gravitate to work similar to your own?

Batt: I find that I read about equal amounts fiction and nonfiction, some older/canonical work and a healthy amount of poetry, too. And I don't know if it's overly self-congratulatory or just silly or what, but I wish I could find more folks who write like I think I do. What and how that is I don't guess is really for me to say, but I think the blessing and the curse of how I write is that I don't feel terribly under any one or two writer's sway.

Miller: Well, my tastes in reading are constantly changing, but I've been reading poetry for many years, so I tend to gravitate toward work that is utterly different from mine, work that I don't understand completely yet but which presents me with a philosophical and/or aesthetic challenge. But I also like returning to older poetry because it changes as I do, and I see new things in it at different stages of my own development as a writer. My biggest fear as a writer is getting to some level of skill and staying there. There is always room for growth, and I'd take as my model a poet like Adrienne Rich who kept reinventing herself as a poet with every new book!

How is the experience of listening to a writer read his or her own words different from reading them on the page?

Batt: I think the best writers can make their work shimmer right off the page without you needing to hear him/her, but, that said, it's always fascinating to hear someone read from his/her own work. As one of my friends puts it, reading is an inherently complicated process – the eye translates the page upside down and backward through the optic nerve to the brain … a lot of translation is happening – but when you hear it, that's about as direct a transmission as it gets.

Miller: With poetry, the experience of listening is pretty essential because the best poems have real music – rhythms and sound echoes that work with and against sentence structures to produce a complex auditory experience. On the page, these aspects are backgrounded because line breaks are often visual in nature, so the page and the stage offer entirely different, but I hope complementary, experiences of a poem. It's really necessary to have both to get the fullness of a poem, and once you've gone to dozens of poetry readings, as poets do, you begin to "hear" things while you read them on a page, so you form a kind of "stereo" habit of reading.

Tell us about your writing habits. Has parenthood changed how you write?

Batt: When I'm actively working on a project, I can pretty much do it anywhere, any time. No incense, stinky candles or fancy berets necessary. I try to abide by the 500-word-a-day rule. That's like a long email or the equivalent of a couple of Facebook posts. Low stakes, in other words. But it's long enough that, if you do it every day or so, you can write a book a year. Of course, the editing and revision process isn't included there, but still. I like how it takes the mysticism out of the process and really just makes it what it is: the daily striving toward a long-term goal. As far as fatherhood and writing, yes and no. I still have lots of other nonparenthood projects I'm developing, but there's something so profound about parenthood that, for a nonfiction writer like me, I feel supremely compelled to write about. At the same time, knowing that my son isn't just a hobby or a source of fascination but rather a person who deserves to have his identity unencumbered by my writing … it gives me pause.

Miller: My writing habits are a little boring and predictable, I am afraid, but I know very well what they are: It must be morning, and it must be quiet. Absolutely no music; music interferes with my hearing of the sounds and rhythms. I do turn off the phone frequently, and more importantly, I turn off the Internet connection entirely so I can't check email or get endlessly distracted by looking for something on the Internet. I usually just unplug the modem and make it hard for the world to intrude on me. Believe it or not, I write best when I'm not yet fully awake! Motherhood has most definitely changed my writing schedule. I have fewer mornings when I can go directly to the desk, and my work day is circumscribed by school bus times. On the other hand, my perceptions of the world have been drastically changed by my role as a parent, and my child's developing mind has offered me new ways of seeing and observing that would never have occurred to me as a woman.

Has writing gotten easier for you over the span of your career?

Batt: I feel like it's gotten more goal-oriented and less imitative. I started out writing a lot of watered-down fiction where I was trying to sound like Ray Carver or Hemingway or Andre Dubus. Over the years I feel like now I know what my point of view is and what I sound like on the page and it's been extremely liberating if not actually easier.

Miller: Believe it or not, I think writing poetry has become harder. The more good poems I read, the more inadequate I feel about making something equal to them, and the more I know about what works, the more I doubt what I produce. On the other hand, there is much less pressure on me now to publish, so I can take my time and revise work for months and even years before anyone else sees it. This doesn't make the work easier, but I hope it makes it better. It gives me plenty of time, anyway, to get distance on a poem before I move it out of the intimate space of my own desk and into the public work of publishing.

Do you write anything other than nonfiction/poetry?

Batt: I started off as a fiction writer and remain an ardent fan of the short story and I have a lot of ideas for a novel that have been percolating for some time. But, then again, who doesn't?

Miller: Yes, I write essays, too, mostly essays about reading poetry, writing poetry, being a writer. I've written fiction as well, but it's often the case that once I start a prose project, I can't help moving it over into poetry. I have a few plays in the drawer, too, but I so love the concentration and music of poetry that pretty much all my best ideas end up in that form sooner or later.

Do you have a favorite piece that you've written? Or something by another writer that you read over and over again? If so, what keeps drawing you back to it?

Batt: I suppose I am pretty pleased with my essay "The Path of Righteousness" about baking sourdough bread and, you know, the fear of parenthood. And in an oddly similar way, despite the vast differences in subject matter, I come back almost annually to Jo Anne Beard's "The Fourth State of Matter" and David Foster Wallace's "Ticket to the Fair." They both do an astonishing job of taking a public event and making it deeply personal and vice versa. And, in a lot of ways, I think that's what the best nonfiction writers are always after. Not just pathetic navel gazing but finding a meaningful and literary way to suture the public and the private.

Miller: I don't have a single favorite poem of my own, though there are always one or two in a book of which I feel most proud. Generally, they are the poems where I figured out how to say or do something that I was struggling with throughout the process of writing the book, but they're not necessarily the best poems in the book. As far as another writer goes, that one is easy: I go back to Ranier Maria Rilke all the time, and he never fails, even in translation, to surprise and inspire me. His poems achieve a special balance of tantalizing mystery and utter clarity, and that's a balance I seek in my own poems as well as in what I tend to read.

Do you see any pattern(s) or recurring themes throughout your body of work?

Batt: Without overthinking it (to which I am prone) I would say the fear of/attraction to commitment to huge responsibilities and/or challenges. It seems to me we live in a relatively low-stakes world where we can pretty readily make a life out of not really striving for anything. That sounds pompous, I know, but how often in your daily experiences do you encounter someone who seems to be really driven toward something important and meaningful to them? I do sometimes, but mostly not. I know I am daily tempted to do the same and often just fall right in line. But in my writing and the aspects of my life I like to write about I find myself drawn to extreme commitments and extraordinary challenges. All the better if I'm not particularly equipped or prepared for it, right?!

Miller: Patterns … yes, I tend to hover around a loose iambic pentameter line, not always, but quite often that kind of line seems most natural to me, most capable of rendering complex philosophical investigations at the same time that it remains musical. When I am in that pattern, it's much easier to trust the language to take me where I need to be.

As for themes, well, I'd leave articulating those to readers, though I can say that there is a strong feminist vision in all of my collections. I can't say that I ever intended that, but having been an undergraduate at an all-female college in the mid-1970s (Stephens College), my first encounters with an intellectual tradition were all imbued with feminist perspectives, and they have stayed with me.

What is the most memorable experience that's happened at one of your readings?

Batt: When I read in Seattle, this guy showed up to hear Francine du Plessix Gray. She read the night before – I went and she was absolutely magisterial. You'd never confuse me for her. But this guy was patient enough to check out the description of my event and it turned out that he had not only lived in the Salt Lake City neighborhood in which my book is set, but he had worked at the King's English Bookstore where I was headed the next day. Nutty!

Miller: I'd have to say that one of the best reading experiences I've had was reading from my last collection, The Resurrection Trade, to an audience of medical students in training. It was a large audience, and the images on which those poems were based were projected on huge screens all around me, but what was most delightful was the fact that at the end, so many of these young doctors in training came up to talk to me afterward. They knew my subject matter from a medical perspective and were excited to experience it from another perspective. Even though many of them had never studied poetry, they were an audience of bright minds, and their immediate and complex understandings of the poetry just bowled me over!

What are you working on now?

Batt: I just finished putting in a new kitchen floor. That was one onerous and long job, and I honestly hope I'll never do something like that again! As for writing, I'm working on what I hope to be the final piece of a collection of essays called The Enthusiast. The manuscript deals with both personal and cultural obsessions with extremity, whether in the realm of bread baking or toddler-wrangling or more ostensibly exotic or athletic pursuits such as cave diving in Central America or ultra long-distance running. Meanwhile, I pray, no more home work!

Tell us some background information about Y.

Miller: This is the hardest of your questions to answer because the book itself is the answer to the questions I sought to explore, and if it could have been done in prose, I would not have needed to write the poems! But I can say that Y brings together a few seemingly disparate areas of subject matter that seemed intimately related to me the more I wrote the poems: First, the Y chromosome itself, its portrayal in popular culture and science, the mysteries that surround it – and, of course, its connection to the development, physical, emotional and cognitive, of boys. Along the way, I also ended up reading a great deal about both fabled and real "wild" children, most notably, Victor of Avyron, the child found in the woods of France whose story was the basis of Francois Truffaut's film "The Wild Child," as well as accounts of teaching young boys to sing, medical accounts of physical changes boys undergo and accounts of how infants learn language, including how we read the human face. I know that sounds like a lot, but the book is an attempt to bring many of these interdisciplinary forays into the same space. And ultimately, the poems aim to enlarge the kinds of questions we ask about childhood and its role in the broader human culture.

There are 16 sets of notes at intervals through the book called "adversaria," a term which generally references a miscellany of notes. I chose it because it did not have the strict definition we normally ascribe to epigraphs, footnotes or endnotes. The adversaria are meant to accompany the sets of poems they frame and to provide a kind of through-line for the book as a whole. I was talking the other day with an interviewer (Amy Goetzman who did the excellent interview/article on Y for MinnPost, "Brought to You by the Letter Y: Leslie Adrienne Miller's New Poems"), and she described the adversaria as "keys" to unlock the book. Exactly. I love that description!