What could a group of St. Thomas alumni possibly have in common with 16th century genius Leonardo da Vinci? The answer is that the alumni – with their various occupations in medicine, finance and technology – are forwarding the application of robotic technology in the treatment of prostate cancer and possibly heart surgery.

The work is done with a robotic system named after daVinci.

And robotics will be a large part of future medical practice.

“The da Vinci system is in its infancy as far as minimally invasive surgery is concerned,” said Dr. Robert Gaertner, who graduated from St. Thomas in 1983 and then from Georgetown Medical School. “There will be new generations of machines based on this one that will be applicable to other surgical specialties.”

John Bannigan, class of 1958 and president of the St. Thomas Alumni Association board, was the perfect patient for this procedure. A lawyer for 40 years, Bannigan, 69, researched the disease when diagnosed with prostate cancer at his January 2005 physical. He got two opinions and decided to go with Gaertner and partner Dr. Chris Knoedler ’84 and the da Vinci surgery.

“I’m a guy who believes in high tech and was intrigued by the robotic part of it,” he said.

“Frankly, people waste a lot of time worrying. If you accept what God has given you and get to work to handle it, life is less stressful. I have a very deep faith that everything that happens is intended and nothing is chance, so I am willing to go along with the program.”

Screening recommended

The program included knowing that prostate cancer, if caught early, has a 90 percent survival rate. A screening (a blood test alone or – ideally – a blood test and a rectal exam) is recommended after age 50 for men because the cancer often produces no symptoms. The leading cancer among men, it is diagnosed in about 3,500 men in Minnesota each year and becomes more common as men age.

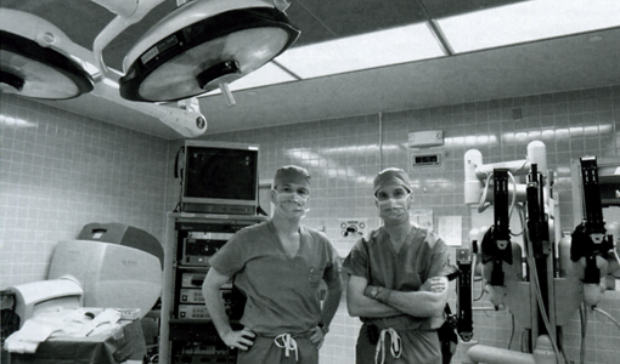

Bannigan’s program also included Gaertner and Knoedler, who are considered expert surgeons in the treatment of prostate cancer and specifically in the effective use of a robotic-assisted surgery system called the da Vinci System. (Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519, may have designed the first known robot, according to the system’s manufacturer, Intuit Surgery Co. of Sunnyvale, Calif. Gaertner and Knoedler use the system at St. John’s Hospital in Maplewood, part of the HealthEast Care System. Fairview University Medical Center also uses the system, as do a few hundred hospitals across the country.

“This da Vinci system, I believe, is the first generation of robotic surgical instrumentation. It will be adapted to become smaller and more versatile. I think this is the future,” said Knoedler, who graduated from the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1984. “There’s no question that patients recover faster, with the majority going home the next day and returning to normal activities in two to three weeks.”

Da Vinci allows doctors to perform prostate cancer surgery less invasively and more effectively by means of robotic arms to simulate physician’s hand movements through five or six small incisions (about the size of a dime) into which necessary surgical tools are inserted. One tool provides a 3-D enhancement for the surgeons’ vision; others include a curved scissors, forceps, needle drivers and cautery hook. Doctors can see better, make smaller cuts, and patients experience less blood loss (900 ccs with traditional surgery but around 75 ccs with da Vinci) and improved recovery times.

The surgeon sits at a console and controls the tools with joysticks; the system cannot move on its own. His hands never enter the patient.

Bannigan’s recovery

Bannigan’s surgery was delayed by other health difficulties – his heart disease, cancer (multiple myeloma in remission after a stem cell transplant), possibly lymphoma and infection from a depressed immune system. But after the prostate surgery on Nov. 1, 2005, Bannigan was in the hospital two nights and was “completely functional when going home.” The most common risks of this surgery are impotence and incontinence, said Bannigan, and “so far, patients of these two surgeons have not had problems with either risk.

“I was recovering fast for two weeks – instead of the two months it took my friends who had what we call ‘big slash’ surgery, which cuts the muscles of the stomach – but then my gall bladder decided it had to come out. Now I have six dime-sized laparoscopic scars from the prostate surgery and three from the gall bladder, which really ruin my chances of ever wearing a Speedo swimsuit.”

Fully recovered now, Bannigan likes to walk – and he means hike, such as his January stroll from United Hospital near downtown St. Paul to St. Thomas five miles away, where he lives a block from campus. He and his wife, Meg, who was a St. Thomas librarian for 35 years, have three children. Two sons, John ’85 and Brendan ’89, work in the Development Office at St. Thomas. Daughter Molly graduated from St. Catherine.

“On the whole, the less intrusive surgery is, the better, though I understand that laparoscopic can’t be done in all cases,” Bannigan said. “I was amazed at how organized and efficient the whole four-hour procedure was. If you can term a procedure elegant, this was. I think the Twin Cities typically has doctors with some of the best reputations and most advanced technology. We are fortunate to live in this area.”

And Bannigan is a survivor. Joking about his medical problems of the last few years, he said, “I do have lots of new friends whose names end in M.D.”

St. Thomas connections

The St. Thomas connection continues in that alumnus Christopher Joslin ’92 is the Twin Cities sales manager for Intuit. Joslin works with Gaertner and Knoedler in placing the high tech surgical system, manufactured in 1998, in hospitals where the doctors practice.

Another alumnus involved is William P. Kelly ’80, a principal with First Premier Capital Leasing Co., which provided the financing for the purchase of the da Vinci systems.

Of all those alumni, Knoedler recalls that he knew only Kelly at St. Thomas. “We played golf together in college. I didn’t have time to play much but Bill was captain of the team,” he said. Knoedler, a Duluth native, is one of 10 children; both his parents were physicians as are four of the children, and one is an R.N. “Our inspiration for medicine came from my dad,” he said. “He loved his profession.” Knoedler is married to a radiologist, also from a family of 10 children, who he met at the Cleveland Clinic where both trained. They have four children.

Three more Knoedlers – brother Dr. John ’73, M.D., Therese ’82 and Beatrice ’87 (married to Steve Sears ’88) – graduated from St. Thomas. “We have a big family connection with the university,” he said, recalling fondly “great teachers” like Drs. Bill Silverman, Nancy Hartung and Father William O’Neill (“a wonderful human being”). His best class was logic with Dr. Tom Sullivan: “It helped me organize my thinking process. If I had to do it over again, I would take more philosophy classes.”

Gaertner agreed that St. Thomas did a good preparation job “for the rigors of medical school. The volume of work and the subject matter were of no surprise when I got to Georgetown.” After a residency at Massachusetts General Hospital and practicing in Scottsdale, Ariz., Gaertner, his wife and two children returned to the Twin Cities. “I knew Chris Knoedler by reputation before joining the group,” he said.

The daVinci system, both predict, is just the beginning in a change of surgery techniques and eventually most surgery will have some robotic instrumentation involved.