Each of St. Thomas’ alumni has a unique story. Helen Love brought hers – and a little-known piece of St. Thomas history – to the forefront when she attended an alumni event in Denver last December. Her name tag was the first indication: Helen Love ’54.

There was some confusion for the event’s organizers as St. Thomas didn’t become coeducational until 1977 – nearly a quarter century after Love’s purported graduation year. (There was some confusion for Love too; she actually earned her bachelor’s degree in 1957, only 20 years before women were “officially” allowed on campus.)

“When you get your degree piecemeal like I did, it can be kind of hard to keep track,” Love said.

“Piecemeal” is just one of the ways you could describe the story of how Love earned a bachelor’s degree. Another way is “rare”: Love is one of just 60 women who received their bachelor’s degree before St. Thomas went coed, and many of those women are now deceased. Another way is “unknown”: It’s not exactly common knowledge that women were conferred degrees at St. Thomas prior to 1981.

Yet there she was, 85 years old and appearing seemingly out of nowhere because she felt meeting the university’s first female president – Dr. Julie Sullivan – was important. Love represents a group of women who showed why the desire for education should be respected and rewarded. And she brought forward a piece of St. Thomas history that shows how an all-male college helped many women realize their educational aspirations.

History of Women at St. Thomas

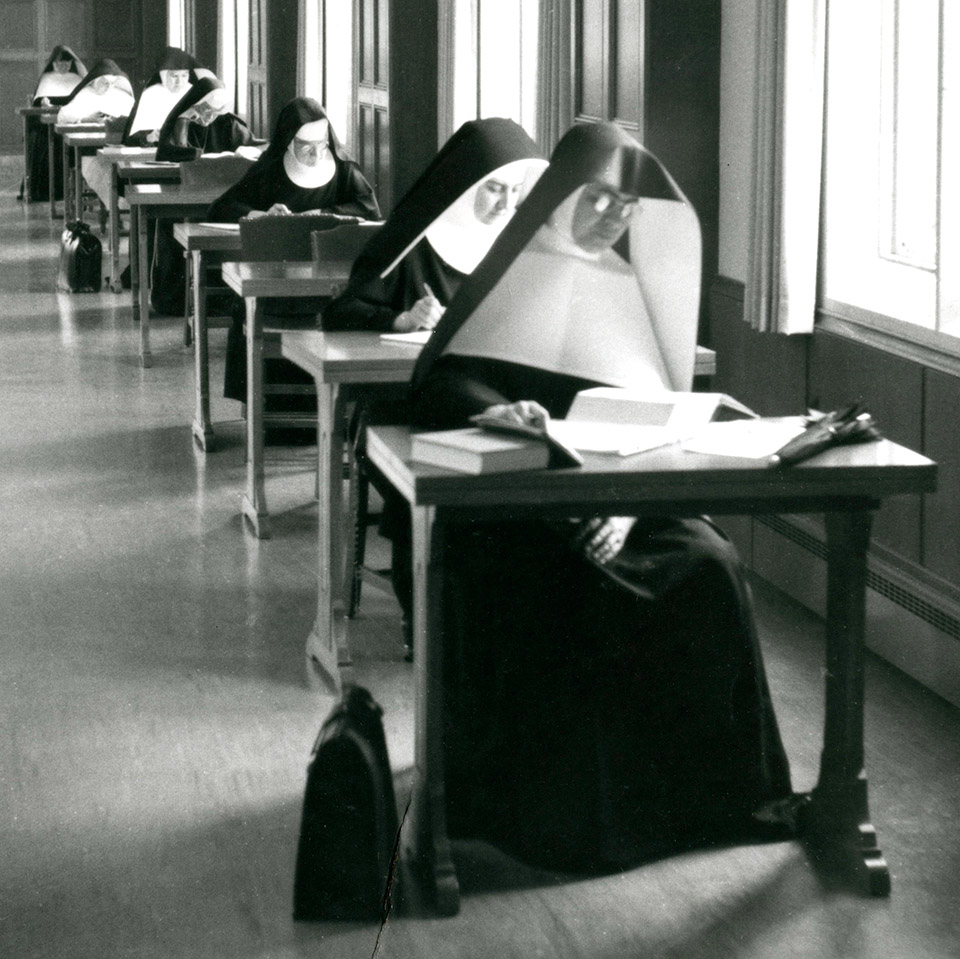

Dig into the list of St. Thomas’ alumni and you’ll find the names Margaret Burke and Agnes Mahoney, the first two women graduates, earning degrees in science and English, respectively, in 1922. Both their names have a “Sr.” designation in front of them, a common signifier before the names of women degree-holders. It stands for sister: Nuns represent the majority of St. Thomas early female alums.

The opportunity for them to attend St. Thomas was possible thanks to agreements between the leaders of local orders and those at the college. Letters between those leaders document the arrangements that, for several decades, saw nuns continue their education at the all-male school.

“Dear Reverend Father: As our Mother Provincial is planning to have several sisters return from the missions to take up the studies of the next semester, we are again calling upon your kind help in planning the courses,” writes Sister Mary of the Convent of the Good Shepherd to the college’s dean, the Rev. William E. O’Donnell, on July 22, 1947.

“Dear Sister Jane Margaret: Enclosed are official schedule blanks for the registration of nuns from the Convent taking courses through St. Thomas,” reads another letter from the St. Thomas records office to the Convent of The Visitation on May 18, 1956.

In 1951, most of the female Master of Education students were nuns.

Burke and Mahoney were as under the radar as degree recipients can be; officially, 1923 was the first year the college offered classes for any women. A Sept. 28 article from the student newspaper, The Aquin, reads, “A Night School of Commerce has been instituted. ... The classes are open to both men and women – to anyone who wishes to develop mentally. This is the first time that anyone but men have come to the College of St. Thomas to attend classes.”

Most nuns took courses through a combination of methods: St. Thomas professors would come to the schools where the sisters taught; the sisters would meet with professors independently, similar to an independent study; and the sisters would attend classes on campus at night and on the weekends. This was still the case when Love, as well as Helen Nalodka (B.A. in history, ’63) and Barbara Peterson (B.A. in sociology, ’58) arrived.

“The teachers were so sweet,” Peterson said. “They were very kind and considerate.”

“You would feel a little bit like an odd duck sometimes [on campus] as a woman, but most times they made you feel very welcome,” Nalodka added. “There was comfort from individual students and the professors were always so kind. I don’t recall a teacher who wasn’t understanding or didn’t do something extra if you needed it.”

St. Thomas launched a Master of Education degree in 1950 that was open to both men and women, so by that time women on campus were a more common sight. More than 900 women would receive their master’s through that program before 1977, the vast majority of them nuns. More quietly, though, the tradition of women collecting their requirements to earn bachelor’s degrees continued on throughout those same years. As Love and Nalodka can attest, it wasn’t necessarily an easy path to take.

Work, Work and More Work

After a year at Mankato State, Love joined the School Sisters of Notre Dame and eventually began teaching at St. Francis de Sales in St. Paul in summer 1953. Further education for the sisters fit in well with the convent’s mission, which Love appreciated.

“The School Sisters of Notre Dame, that was their whole thing: They wanted to be good teachers,” Love said. “In the 1950s before high school accreditation and all that, it was allowed [that you taught even if] you didn’t have your degree to teach. We wanted more than that.”

Love attended class on Saturdays and mixed with both men and women, the latter of which were studying mainly for their master’s in education.

Their schedules were perhaps the most difficult thing to negotiate: Love taught both fifth and sixth grade while completing her studies, along with all the day-to-day responsibilities in her order.

“It was hard. Especially when you’re not a seasoned teacher. You had to prepare your classes, spending a lot of time going over that on Sundays for the whole week. Then you [had] to get your prayers in, cleaning duties, other duties. We kept really busy,” Love said. “We got flashlights because our mother would throw the electricity switch [at the convent]. Every night we would beg to stay up later, leave the lights on. She was pretty sure we needed more sleep and she didn’t know how long we’d use our flashlights.

Click for a list of notable female occurrences at an all-male college

1922: First bachelor's degrees conferred to women.

1923: Night School of Commerce opens for men and women.

1948: Mary Keef becomes school's first full-time female faculty member.

1950: Master of Education program opens for men and women.

1951: Sister Maria Stephen Lamm becomes first female to receive master's degree from St. Thomas.

1977: Connie Pocrnich is first female student admitted after the college becomes coeducational.

“I know as I got closer [to completing my degree] I was happy to think that even though it looked piecemeal, all the pieces were coming into one quilt, so to speak,” Love added. “I was really happy to have [my degree] completed.”

Nights, weekends and summers also were key for Nalodka, a Toledo, Ohio, native who began taking courses at St. Thomas as a Sister of St. Francis a few years after Love earned her degree in 1957. After taking classes from a St. Thomas professor who would come to where she was teaching – Holy Cross Elementary on University Avenue – Nalodka continued pursuing a history degree with courses on campus in the summer and evenings.

“We weren’t permitted [by our convent] at certain times to go to the library, so I remember I prized Monsignor Nicholas Molter because he gave me lots of books. He and many professors went out of their way to help you,” Nalodka said. “I never really thought about us being coed. We just went along with it back then; you didn’t challenge some of those ideas.”

Both Love and Nalodka continued their educations after they left St. Thomas: Love received a degree in French from Laval University in Quebec and Nalodka earned her master’s in rehabilitation counseling from Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Both ended up leaving their orders in the years following the Second Vatican Council, which stirred up many changes in Catholic orders throughout the world. Love continued teaching until she went back to nursing school and worked in health care before retiring in 2005; Nalodka was a counselor, then the director of a senior center before she finished her career working for the state of Ohio.

For both, the opportunities they were afforded at St. Thomas helped launch legacies of lifelong learning that carried them throughout the decades. Nalodka said she loved traveling and learning about other countries, but one stop in particular meant a lot: Her love of Greek history was stoked in her courses at St. Thomas, and in 1990 she fulfilled her lifelong dream of visiting Greece. She spoke at length about the beauty of her experience there, the hanging baskets and rich history she had learned about in her studies.

“Education has always been important in our family,” said Nalodka, whose mother came from Ukraine and couldn’t read or write. “I always have encouraged women to go on to more learning, more education, whatever possible to better yourself. I’m always trying to instill that in my nieces and nephews.”

A Lasting Connection

Nalodka hasn’t kept in touch with St. Thomas much through the years; she said she hasn’t been back since her graduation in 1963, but still has her commencement program and pictures from her time here. Love has kept in touch more, returning to campus in 2000 after attending a gathering of the School Sisters of Notre Dame to show her husband, Richard, where she went to school.

“I had no idea how much it had grown,” she said. “When I think back, we were only about 800 students in the ’50s. To hear that you’re 10,000 students now is really amazing.”

The evolution of St. Thomas was a topic of conversation between Love and Sullivan when they met in Denver.

“She felt St. Thomas was a very important part of her own formation, and it’s a joy to see its continued growth and development as an institution in ways she really appreciated,” Sullivan said.

Master of Education student Penninah Silverberg receives her academic hood from Leonard Hauser at the College of St. Thomas commencement ceremony, June 1966. Lee Simmons looks on.

Sullivan later acknowledged Love during her speech in Denver, stating to everyone’s surprise that the oldest alum in the room wasn’t a male Tommie. Learning more about Love’s experience and about others like her further cemented a lesson Sullivan said she’s been learning since she arrived at St. Thomas.

“It was one more example of what I’ve seen over and over since the founding of St. Thomas, and that’s the progressiveness of the leaders here,” she said. “It would have been really easy to say, ‘Sorry, we don’t [teach women],’ but clearly, the leaders at the time said, ‘We are all male, but we understand the need for your sisters to be educated and we want to contribute to that.’ That showed a lot of foresight.”

In a final serendipitous connection, Sullivan was approached last year to speak to the School Sisters of Notre Dame on campus in March, when they came to St. Thomas for a women’s leadership luncheon. Sullivan spoke of the need to advance the common good, a bond that already has been shared between the two groups through those like Love.

“You see things that have happened at St. Thomas throughout the decades under different leaders who have exhibited a lot of vision and foresight. And willingness to think about something differently. [These women getting their degrees] is another one of those examples,” Sullivan said. “It gives you a real inspiration.”

Read more from St. Thomas magazine.