Artificial intelligence (AI) has become ubiquitous with a growing number of consumer gadgets being connected and “smart,” from smartwatches, Alexa, Siri, Netflix and Amazon recommendation algorithms, industrial IoT applications and abbreviated answers to your email based on context. In an effort for companies to ride this technology wave, they are rushing to transform themselves into “AI-first” organizations, pouring massive R&D time and dollars (or yuan/euros/pounds…) into this technology. You read the headlines almost daily – reports on how the United States and China are competing for supremacy in this field – a race to the top ... but what does that mean, really?

The analysis of dominance with respect to an enabling technology like AI must account for two factors – companies and markets. AI tech is not a trade good like, say, coffee, where Brazil and Vietnam may compete for market supremacy that you can measure in metric tons. It’s even difficult to compare to other high technology like the semiconductor chip market because there is no tangible trade good to track. Supremacy when it comes to AI technology has to be measured in the value created by the technology itself. In many cases, this technology gets implemented in downstream products which are bought and sold, signaling value. If we compare nations, AI supremacy is not just about having a trophy on the wall and feeling good about some neat algorithms having been conceived of within a country's borders.

The analysis of dominance with respect to an enabling technology like AI must account for two factors – companies and markets. AI tech is not a trade good like, say, coffee, where Brazil and Vietnam may compete for market supremacy that you can measure in metric tons. It’s even difficult to compare to other high technology like the semiconductor chip market because there is no tangible trade good to track. Supremacy when it comes to AI technology has to be measured in the value created by the technology itself. In many cases, this technology gets implemented in downstream products which are bought and sold, signaling value. If we compare nations, AI supremacy is not just about having a trophy on the wall and feeling good about some neat algorithms having been conceived of within a country's borders.

Scholars Brynjolfsson & Mitchell: “no widely shared agreement on the tasks where machine learning systems excel, and thus little agreement on the expected impacts on the workforce and the economy more broadly.”

AI dominance can be defined by companies in a country making valuable AI technologies and monetizing them to drive national economic growth.

Economic and potential value

Sector dominance really must come down to economics. When U.S. companies sell a number of goods generating some amount of revenue, there is real measurable benefit to the national economy. This is especially true when talking about end-product sales and exports. The end-product analysis is an important one because there is a reduced benefit from creating a component which is exported and sold for an amount but is incorporated into an end product which may be reimported with a markup. In that scenario there is a net outflow of cash from the nation of the component origin. This gives us the first part of the analysis – current value – where the end products are sold, and where that revenue flows.

For the second part, we want to identify potential for value. This analysis starts with talent and the technology itself. Admittedly, these are hard things to objectively measure. This is why it is easy for countries to make claims about technology leadership in areas like AI. Fact-checking becomes a difficult and very subjective endeavor. Intellectual property, however, provides a very interesting source of data – patent data in particular. Patents are a great resource for discovering what is being developed, what has been developed and what is at least worth the money and effort to secure that monopoly. They are also chock full of data – from a patent filing, we can tell the owner (and country), the inventors – the talent, and their location, and of course, detailed descriptions of the technology.

Intellectual property as data

The best part is that this information is all publicly available by law and treaty, across the world. Here is how it works: Every patent is a trade – a quid pro quo – a government offers this limited monopoly (the carrot) explaining, in detail, how the invention works. Detail is important, enough detail that a peer could read that description and understand how to replicate the work. This all gets published publicly to the rest of world. This is a key point – not just because it provides access to the data, but we will get back to that.

Another key point – patents are geographic – meaning that you have to apply for one in each country where you want protection. Thanks to some broad-reaching international treaties, pretty much every country in the world participates. Each country’s intellectual property system operates in a similar way, that is, the inventor must describe his/her invention and then let the patent office publish it in exchange for a limited monopoly in that country. From that patent data or filing, this is how one can get access to nation-level patent filings. That data serves as an indicator of the value of jurisdictions – and ultimately the value of the market, within that country. In addition, there is visibility to see who is filing as well as how much they are filing. From all that information, you can decipher what they are protecting and what markets are valuable enough to justify the costs associated with that protection.

Let’s return to the idea of companies and markets driving a value determination. AI supremacy can be defined by companies in a particular country making valuable AI technologies and monetizing them to drive national economic growth. Economic growth means monetary and ecosystem value increases. From a market perspective, the ecosystem component is quite important. The availability of talent, enabling components, infrastructure, data and empowering technologies all facilitate further growth.

Insights in the data

Leveraging AI IP data, we want to focus on those technologies which are foundational and those which are implementational. Foundational technologies are the underlying technologies and inventions that power the space. Think algorithms, process procedures, architectures ... the types of ideas that are generally application-agnostic but empower all kinds of end products. Deep learning networks, reinforcement learning processes and neural processing units (NPUs), these are good examples – developments and improvements in this space provide the foundations for implementations. Implementational technologies then leverage the underlying technologies with data, interface, user variables and other factors to provide a benefit for the customer. Think chatbots or autonomous vehicles. The results of the analysis show that the data shows that U.S. companies hold the majority of foundational IP. Does that mean that the U.S. has dominance? No. However, we must consider it a factor though. It should be noted that there are other forms of IP rights that we cannot track. Trade secret developments, which tend to live in the foundational tech space, will never be publicly quantifiable, but add another variable.

The analysis should want to look at a few factors combined. Where patents are being filed – to determine market value. Where the companies filing these patents reside – to determine economic impact. Which are foundational and implementational – to determine enablement and end application. Finally, where the technologists/inventors reside – to determine the resources of the ecosystem. From these points, we can make some pretty good determinations. Thankfully, all of the data for this analysis exists and is publicly available through patent data.

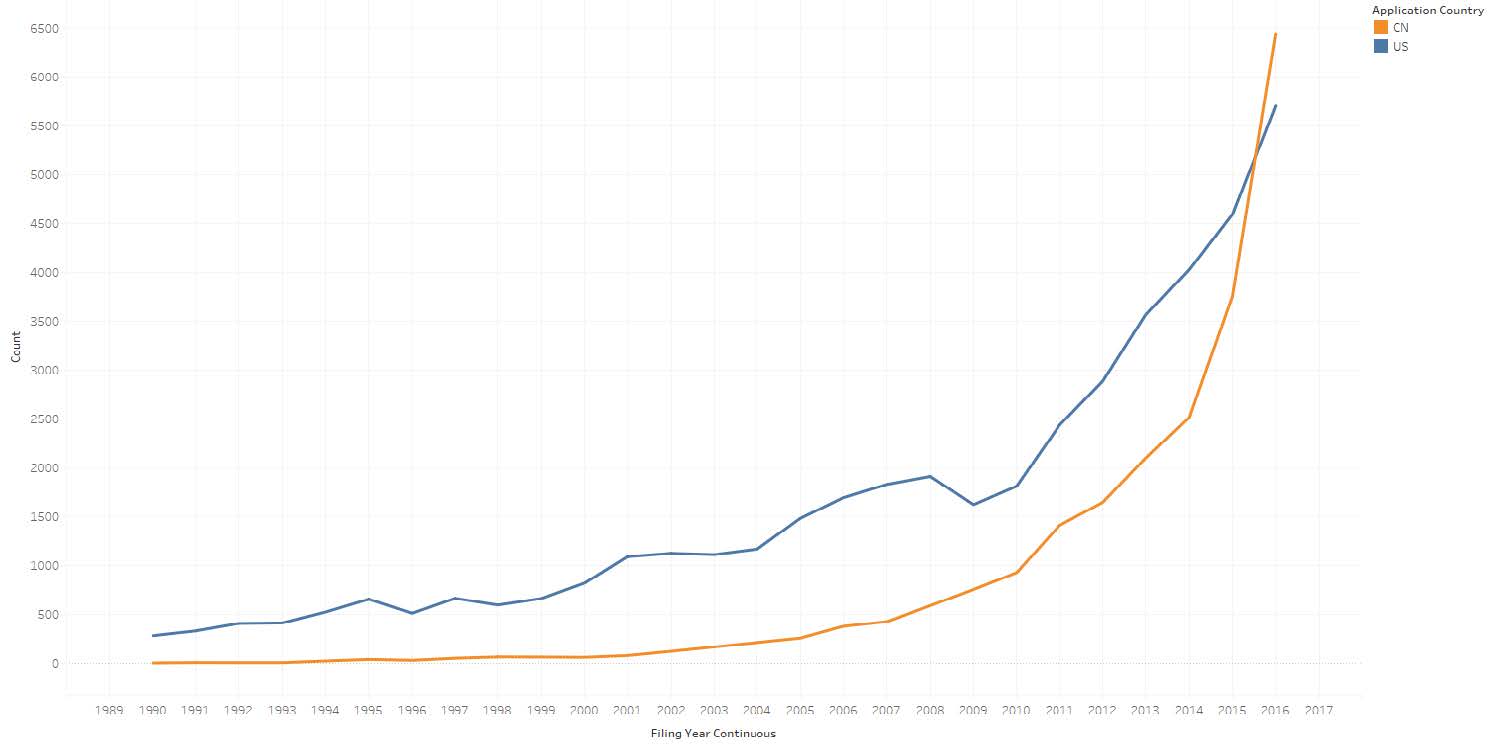

Here is how it shakes out. From a dataset of over 100 million patents globally, around 200,000 were identified specifically in the artificial intelligence space. The data shows that there are an increasing number of patent applications being filed in China (Figure 1). In fact, back in 2016 China surpassed the U.S. to be the country receiving the most patent filings. This could be an indicator of AI dominance, and digging into the data, we see that nearly 20% of these filings originate from abroad.

Figure 1: Patent applications in China and U.S.

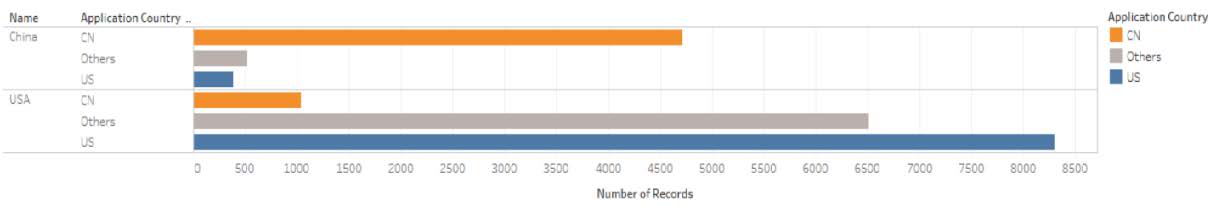

Filing strategies by China and USA

When looking at the patenting strategies of Chinese companies compared to U.S. – the difference is palpable. Chinese companies are filing fewer patents, and of those, the patents are mostly domestic. This is in contrast to U.S. companies, which have a more balanced domestic-international split.

Figure 2: China and USA domestic and international AI patent filings

Finally, the data also shows that the highest concentration of AI invention (development of new technologies) is being done by inventors residing in the U.S. It is worth noting, however, that in the 1990s, China was not on even on the map. In the 2000s, they leaped to the forefront, landing in the top four. The last decade places China in the No. 2 position. That is some serious progress which cannot be ignored.

Before we go projecting China’s AI dominance based on this trend, there is a subtle but important variable to factor in. AI technology talent and resources are growing in China. The IP strategies of Chinese technology companies, however, remain heavily domestic. This fact will encumber the overall AI competitiveness growth trajectory. New technologies being developed are less capable to drive foreign sourced revenue when they lack that foreign market IP protection. Of course, growth impact is only part of the issue. Strong technology development paired with weak IP protection makes those ideas vulnerable to copying by other players in international markets. This means that the R&D effort and dollars spent can actually be fueling outside growth.

Another way to look at this issue is by first understanding that the initial value of most AI technologies relies on how it is used more so than how it is constructed. Take coal fields as an analogy. Just because coal was mined in one place, this does not mean that place is where the peak economic value was created. Instead, we follow the coal to where it is used – areas where the steam engines and the factories were based. AI algorithms and underlying technologies have the same dynamic. Extraction in China, for example, does not mean that China is necessarily where the full economic value is derived. Certainly there is value to be extracted in Chinese markets, but that leaves a lot on the table with markets and companies in the U.S. and elsewhere across the world.

Globalization

Perhaps trying to compare national dominance in the AI field is becoming more and more difficult in a globalized economy. Identifying where value is being created and true value moments becomes the goal. Realistically, value moments and opportunities occur in market and by citizens and company owners not restricted by or tied to geographic borders. Three-quarters of all the value add found for AI comes from operational easing projects that upend existing CAPEX and OPEX models. These tend to be highly situational and the key IP comes from people, the process and the data. That all makes it pretty difficult for any one market or company to control or dominate on their own.

About the authors

Michael Gale is the chief executive officer of inc.digital, board member, co-author of The Wall Street Journal bestseller The Digital Helix, AI influencer, and podcast host about the world in 2030.

Thomas Marlow is the chief technology officer at Black Hills IP. As a patent attorney and technologist, he is a published author, recognized speaker and expert in the field of intellectual property and technology.

Manjeet Rege, PhD, is the director of the Center for Applied Artificial Intelligence and an associate professor of Graduate Programs in Software and Data Science at the University of St. Thomas. Rege is an author, mentor, thought leader, and a frequent public speaker on big data, machine learning, and AI technologies.

Dan Yarmoluk is an adjunct faculty at the University of St. Thomas, Graduate Programs in Software Engineering, Data Science and member of the Center for Applied Artificial Intelligence. He is a recognized author, entrepreneur and IoT, data science and automation expert.

Read about artificial intelligence and its impact on jobs in this article by Rege and Yarmoluk.

Related Content