The European Union is once again facing a significant financial crisis as Cyprus has pushed Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain from the headlines. How can such a small country – with fewer than one million citizens – have such a large impact on the global economy? The answer is complicated, much like the March 25 bailout agreement between the troika – the European Union, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank (ECB).

The agreement with the Cypriot government paves way for Cyprus to receive a €10 billion bailout. In return, Cyprus has agreed to downsize its large financial sector and undertake a macroeconomic adjustment program that will require fiscal consolidation, structural reforms and privatizations (among other concessions). In return, the ECB will continue to provide emergency liquidity assistance to Cyprus banks.

The most contentious bank levy, demanded earlier by the troika, has been completely scrapped. Deposits in all banks up to the deposit insurance limit of €100,000 will be protected. The second largest bank, Laiki Bank, will be resolved by splitting it into a good and a bad bank. Deposits up to €100,000 will be transferred to the good bank, which will be folded into Bank of Cyprus. Laiki Banks’ equity holders, bond holders and uninsured depositors will remain with the bad bank, which will be resolved. Bank of Cyprus also will be restructured and recapitalized.

The problems at Cyprus banks have been known for some time. A major reason for this predicament is that Cyprus’ banks have suffered great losses due to write-downs on their Greek government bond holdings as a result of Greek debt restructuring last year. The two largest banks – Bank of Cyprus and Laiki Bank – reportedly have suffered losses of about €4 billion. Both the previous Cypriot government and the troika are equally culpable for kicking the can down the road, for perpetuating conditions that could force Cyprus to collapse and exit the European Union.

The economic, social and political implications of the proposed measures are enormous. For the first time, the Eurozone authorities have confirmed that when a member country falls into a banking crisis uninsured bank depositors might have to share losses along with other creditors. This likely creates fear among depositors and leads to a capital flight from the troubled nations such as Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain into stronger countries. A freeze on uninsured deposits, restrictions on withdrawals and capital controls might prevent a big bank run in the short-term, but the damage to Cyprus’s economic model as an off-shore financial center is likely irrevocable.

Although there is no explicit tax on large deposits, uninsured depositors will suffer substantial losses – as much as 60 percent according to some estimates – since they have to share the losses resulting from the resolution of Laiki Bank and the restructuring of Bank of Cyprus. The uninsured depositors might receive shares as settlement for their lost deposits. Given that about one third of €68 billion bank deposits is from outside of the European Union, the Cyprus solution somewhat resembles the Icelandic solution where Icelandic banks defaulted on foreign depositors. But there is one important difference: Iceland is not part of the Eurozone.

The end result is not pretty. Cyprus has been shut out from bond markets for some time. The last time Cyprus issued long-term bonds, investors required a yield of 7 percent. The banking sector is on life support from the ECB through the emergency liquidity assistance program. In an economy where the banking sector is about eight times the size of the economy, a deep liquidity crisis will create a severe blow to the already fragile economy.

The European Union expects the real GDP to decline by 3.5 percent in 2013 and by another 1.3 percent in 2014. Bank and liquidity problems could further deteriorate growth by limiting funding for key business sectors such as tourism, financial services and shipping. Resulting business closures and layoffs will further increase the unemployment rate, which is currently almost 15 percent.

Cyprus has run a budget deficit in excess of 5 percent for the last four years and expects to run similar, if not more, deficits in the foreseeable future. Fiscal adjustments and structural reforms that will be part of the conditionality of the bailout program, and the expected downsizing of the large financial sector will further reduce growth and increase unemployment. All these have the potential to create more social unrest and weaken the position of the new government – which is barely a month old – creating political turbulence when a stable government is necessary for difficult economic reforms.

What is largely ignored in the current debate about Cyprus is its sovereign debt. This is because the debt is only about 84 percent of the GDP, a €18 billion economy with about €15 billion debt. This debt level is the second lowest among the crisis-hit countries, and compares favorably with nations such as Greece (153 percent), Italy (127 percent), Portugal (120 percent), and Ireland (117 percent). But the €10 billion bailout loan will increase debt to 140 percent of the GDP and put Cyprus just behind Greece. Such high level of debt for a smaller economy with increasingly negative growth and budget deficits leads to an inevitable conclusion: Cyprus will not be able to grow out of debt, and this level of debt is not sustainable.

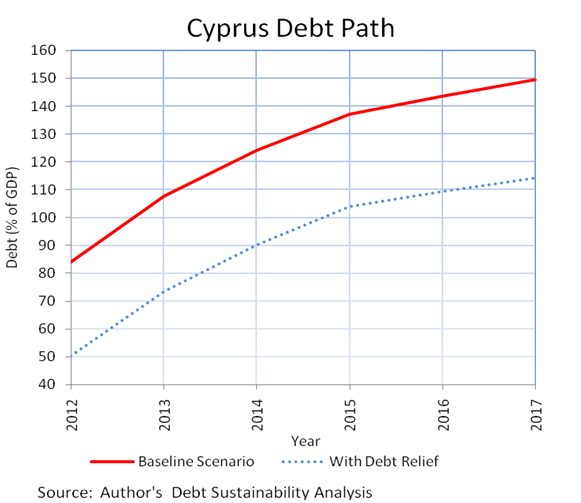

So, what would the debt path for Cyprus look like? Although details of the rescue plan are not yet finalized, the purpose of the bailout is to support debt service payments and budgetary shortfalls. Assuming a three-year disbursement schedule of €4 billion in 2013, €3 billion in 2014, €3 billion in 2015, and the EU and IMF baseline growth, inflation and deficit projection, the debt path for Cyprus takes the form shown in this chart above.

Debt will continue to climb from the current 84 percent to 108 percent by the end of 2013, and to 149 percent by 2017. These debt projections will further worsen if one were to factor in growth declines due to macroeconomic adjustment program and the expected downsizing of the financial sector.

The Cyprus solution clearly leads to an exploding and unsustainable debt path. As in the case of Greece, if the IMF’s target sustainable debt level for Cyprus is 120 percent by 2020, then it will be impossible for Cyprus to achieve it under the forecasted macroeconomic scenario. By any means, 120 percent is not a sustainable level either. This leads to another inevitable conclusion: Cyprus will need a substantial reduction in debt stock through debt relief.

How much debt relief would Cyprus need? Debt stock will need to be trimmed by at least €6 billion to €9 billion, making the current debt-to-GDP ratio 50 percent. With the reduced debt load and the new debt added through the rescue plan, the projected macroeconomic scenario will increase Cyprus’s debt to 114 percent by 2017. With a carefully designed macroeconomic stabilization program that leaves room for growth, Cyprus might be able to show some promise of debt sustainability. Without a “big bath,” Cyprus is looking at decades of unsustainable debt overhang and additional future bailouts.

Lalith Samarakoon is professor and chair of the Department of Finance in the Opus College of Business. As a financial economist, Samarakoon has two decades of advisory experience in financial sector reforms and development, and public debt management. He teaches Global Finance Issues and Policy: Eurozone Debt Crisis.