Solitary confinement for 105 days

Dr. Haleh Esfandiari, an Iranian-American who has lived in the United States since 1980, was robbed of her belongings, including her U.S. and Iranian passports, at knifepoint in 2007 on her way to the airport after her yearly Christmas stay with her mother in Tehran, Iran.

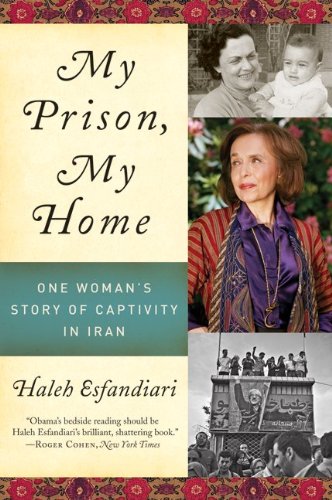

The crime, however, was no ordinary robbery but a staged heist by Iran's Intelligence Ministry to obtain her personal information. Her work as director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (a position she currently holds) aroused the suspicions of the ministry, which eventually accused her of conspiring in an American plot to overthrow the Iranian regime; consequently, she was interrogated for eight months, 105 days of which she spent detained in solitary confinement as a political prisoner in Iran's notorious Evin Prison. She chronicled the ordeal in her 2010 memoir, My Prison, My Home.

A longtime advocate for human rights and women’s rights, Esfandiari is this year's Women's History Month speaker. She will speak on “The Women’s Movement in Iran and the Middle East” at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, March 6, in the auditorium of the O’Shaughnessy Educational Center on the St. Paul campus of the University of St. Thomas.

Her talk will interweave her personal experiences with a political history of Iran and the Middle East, and will discuss the changing situations of the region from an international feminist perspective.

Born in Iran in 1940, Esfandiari received her Ph.D. from the University of Vienna. She taught Persian language and literature at Princeton University from 1980 to 1994, and has directed the Middle East Program at the Wilson center since 1997.

Born in Iran in 1940, Esfandiari received her Ph.D. from the University of Vienna. She taught Persian language and literature at Princeton University from 1980 to 1994, and has directed the Middle East Program at the Wilson center since 1997.

Esfandiari was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Grant and was the first recipient of an award established in her name, the Haleh Esfandiari Award. It now is presented annually by a group of businesswomen and activists from countries across the Middle East and North Africa.

Esfandiari will be available to sign copies of My Prison, My Home following her lecture. Free and open to the public, the Women’s History Month lecture is sponsored by St. Thomas’ Luann Dummer Center for Women.

More information about Esfandiari and the Luann Dummer Center can be found online.

Esfandiari answered questions for the Newsroom last week via email about her imprisonment and work.

The conversation

Have you been back to Iran since you left following your imprisonment? What would it take for you to return, especially since your mother passed away?

No, I have not been back to Iran since September 2007, when I left the country. As I explain in my book, it was a painful departure. On the one hand I was happy to be free and to go home; on the other I knew that I might not be able to return to Iran for a number of years. For me to return, there would have to be government that would not prosecute and persecute me.

What do you miss most about Iran?

I miss most about Iran the wonderful physical landscape – the majesty of the mountains, the clarity of the night sky – and the warmth of the people.

Your case remained open as of the publication of My Prison, My Home. Is your case still open today?

Yes, my case is still open. I was released on bail, and the bail still stands. This means the Iranian judiciary, which seems never able to close and end a case, can summon me to appear in court any time they wish to.

Are female political prisoners treated differently than male political prisoners in Iran?

No. Basically in Iran male and female political prisoners are not treated differently. But individuals are treated differently depending on their status as prisoners. Some are physically tortured; others are mentally harassed. Some prisoners are put in tiny cells, others in larger ones. Some prisoners, like me, are placed in solitary confinement; others are confined in groups. There is no single pattern.

You were very disciplined during your solitary confinement, mindful of keeping physically active and limiting your television usage when they placed one in your cell, despite your wishes; how important was keeping a routine to your morale and survival?

I did not want to have a television in my cell, but despite my objections, later in my imprisonment, they placed a television set in my room, and I had to endure the physical presence of a large TV in what was already a cramped cell. I would turn it on to watch the news because I had been cut off from any access to the news for quite a while. Did it do something for my morale? Not really. On the contrary, the appearance of the television set caused me concern. I thought it meant they were settling me in for a long stay; however, I was determined from the first day of my confinement not to give in to depression. I imposed on myself a rigorous schedule for each day and stuck to it.

Did you consider yourself a political dissident (with regard to Iran’s government) before your incarceration? What about after your release from Evin?

I am not a political activist; therefore, my arrest, interrogation and incarceration came as a big surprise. I was the victim of the paranoia and conspiratorial mindset of Iran’s Intelligence Ministry. They stole from me a year of my life, and in the end were able to prove nothing; however, I am a feminist and an advocate for women’s rights. I write and speak about the subjugation of women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and believe in total equality for men and women under the law.

In your memoir, you called yourself an "unrepentant feminist." What does that phrase mean to you? How does it play out in your daily life?

I believe in gender equality. I think the constitution of every country should include articles regarding total equality of its citizens regardless of sex, creed and religion. I believe that the constitutions in countries of the MENA region should be revisited and the discrepancies between the rights of male and female citizens should be removed. I believe societies should aim for 50 percent participation by women in political, economic and social life.

What is the current political climate of Iran from your feminist perspective?

The Islamic Republic of Iran is not gender-equality friendly. The history of the women’s movement in the last 35 years in Iran has been a history of constant battle between the government and women. Iranian women are the only group that have systematically pushed back against the government whenever it tried to infringe on their rights. Today Iranian women are far from being equal citizens of Iran, nor do they have the same rights as their male counterparts. But women have made some progress since the early days of the revolution, when most of their rights were suspended. Iranian women sit in parliament but there is no woman minister in the cabinet. The Foreign ministry has a woman spokesperson, but there are no women ambassadors nor deputy ministers. Today, more than 63 percent of entering classes at universities are women, and this has so alarmed the men that parliament is toying with the idea of introducing a quota system in favor of men. There are many similar examples.