Each day hundreds, perhaps thousands, of students walk by the bronze statue of Archbishop John Ireland, which looks out on the lower quad of the campus. While he may be largely forgotten today, when he died in 1918, he was one of the most famous men in Minnesota and a legendary American bishop.

There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, told about John Gregory Murray, a former archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis. One day in the early 1950s, he came into the dining room at the Cathedral of St. Paul rectory, for lunch with some of his priests, with a great smile on his face. “I have just met a man,” he happily told them, “who has never heard of John Ireland!”

It must have been a rare man who Murray met that day, for every one of Ireland’s successors has lived and worked in the shadow of the first archbishop of St. Paul. It is difficult to overestimate the deep formative influence that Ireland exercised on the Church and the larger community in his 43 years as a bishop in Minnesota.

From a rudimentary education to a cultured French seminary

He was, of course, the founder of the University of St. Thomas, a project that was particularly close to his heart and received his very personal attention. He also was responsible for the construction of the present Cathedral, on the highest point of land in St. Paul (to overlook the capitol building), and the Basilica of St. Mary in Minneapolis and established several dioceses and many parishes.

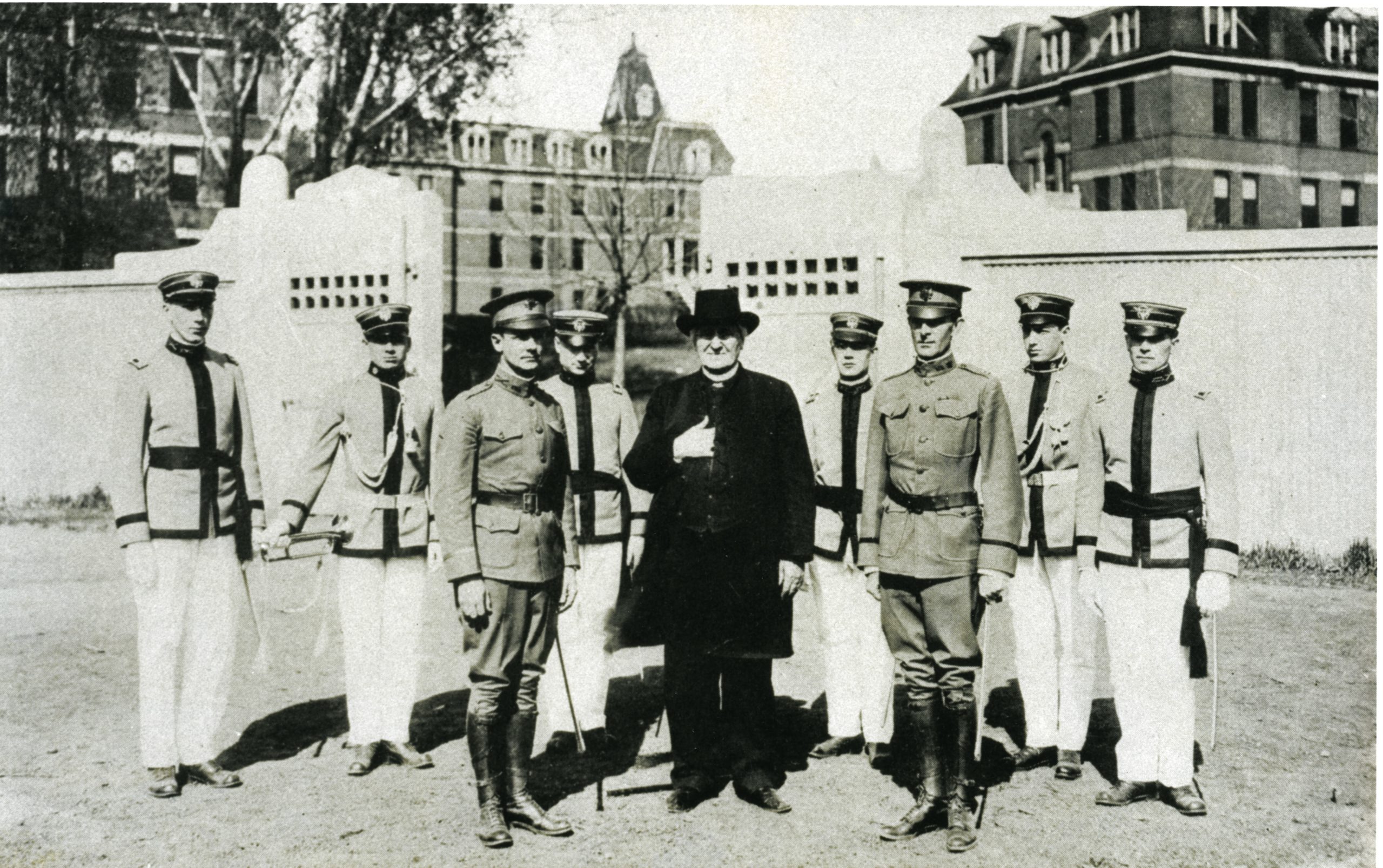

He led a temperance movement, served as the chaplain to a Minnesota regiment in the Civil War, and was the friend of presidents. His energy and boldness were legendary. On one occasion, another bishop described him, with affection, as “the consecrated blizzard of the Northwest,” an image Minnesotans will appreciate. A later writer, however, disagreed and claimed that he was more like a “prairie fire,” valiant, impulsive, idealistic and passionate about projects. Regardless of the image, he was a man not easily forgotten.

John Ireland was born in 1838, a few years before the devastation of the Great Famine, in a small town in southeastern Ireland. His family emigrated to America, settling first in Vermont but by May 1852 moving permanently to St. Paul. At the time, it was a town of perhaps 2,000 residents, many of whom were French (as were virtually all of the clergy). He had had only the most rudimentary education in Ireland and in St. Paul received little more than that. Even so, Joseph Crétin, the French missionary who was the first bishop of the diocese, saw something of promise in the young man. So it was that, in the autumn of 1853, accompanied by the pioneer missionary priest Augustin Ravoux, Ireland and one other Irish boy were sent to study in France, the first seminarians of the Diocese of St. Paul.

When the young and frontier-rough Ireland arrived at the petit séminaire, the minor seminary, at Meximieux, in eastern France, he was unable to speak much French and entirely unfamiliar with the course of study then offered to him. Meximieux was a diocesan seminary, the very school that Crétin himself had attended some decades earlier. As such, it was staffed entirely by priests of the local diocese and oriented toward preparing men for parish service. It offered a classical curriculum – today we would speak of the liberal arts or the humanities – and a strictly disciplined daily schedule.

Though his more cultured French classmates regarded him with amusement at first, two personal characteristics gained him their affection and later their admiration. On the one hand, Ireland was a bold and mischievous boy, who enjoyed his share of practical jokes. But on the other hand, he displayed an energy and intensity for study that was remarkable. He may not have been the very best student of his cohort at Meximieux, but he was certainly among the best. In return, the school nurtured in him not only an appreciation for literature, philosophy and theology but also a deep admiration for academic excellence. For the remainder of his life, Ireland regarded his four years there as among his happiest and most formative.

John Ireland becomes St. Paul’s third bishop

When Ireland left Meximieux in 1857, two years ahead of schedule, it was to enter a grand séminaire, a major, or graduate, seminary, operated by the Marist order in southern France. While he succeeded as a student, his four years there, as one of the very few diocesan seminarians, were not pleasant. The experience seemed to confirm in him a bias against religious orders, which figured prominently in his efforts nearly three decades later to establish the College of St. Thomas and the St. Paul Seminary in his own diocese.

Ireland returned home in the summer of 1861 and was ordained in December of that year by Bishop Thomas Grace, Crétin’s successor. In 1867 he became rector of the Cathedral, and in 1875 was ordained coadjutor bishop of St. Paul, almost 14 years to the day after his ordination to the priesthood. In 1884, Bishop Grace retired and Ireland became the third bishop of St. Paul.

One of the passions that Ireland inherited from both of his predecessors was a determination to foster local Catholic education and a home-grown priesthood. His first effort in this regard was to propose to Bishop Grace that the diocese establish an industrial school, which at that time was the sort of school dedicated to teaching a trade to orphaned and delinquent boys. The school was duly established in 1874 but quickly failed and was closed. However, in the process, Ireland obtained a tract of land from William Finn – after whom St. Thomas’ Finn society is named – whose land would later be put to a more permanent and successful use. That successful use, of course, was ultimately to be the College of St. Thomas.

In December of 1884, immediately after he succeeded Bishop Grace, Ireland announced that he would open a seminary in the diocese the following autumn. He said, exaggerating a bit as it turned out, that the project would be “the principal work” of his episcopacy. Certainly he regarded it as a legacy, the most important thing he could do as bishop to secure the future of the diocese. Still, he had no faculty, no students and little money. But he did have the land from Finn. The foundation of the St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary was entirely in keeping with his willingness to take risks in pursuit of his objectives.

With Meximieux as his model, he knew what he wanted to do. The early history of St. Thomas testifies to this. While in its first decade it was titled a “seminary;” it was, in fact a college of sorts in combination with a prep school. Its curriculum emphasized a classical formation modeled on the one Ireland had received at Meximieux, even though the majority of students did not pursue ordination to priesthood. From the beginning, Ireland was quite explicit about his goals not only for the institution but for Catholic higher education in Minnesota. The preparation of future clergy was a priority, but more broadly he was concerned that Catholics take their place in business, in the professions and generally in the civic life of the community. He was convinced that religion in general, and Catholics in particular, had an indispensable role to play in the life and future of America.

Ireland donates his personal property, but with three conditions

The nine months following Ireland’s announcement were furiously busy as he threw himself into all of the details of establishing the school, from expanding the building to hiring a rector and faculty, to devising a curriculum. True to his word, and to the astonishment of many, the school did open on Sept. 8, 1885. (Two weeks earlier, in order to promote support among the priests of the diocese, Ireland had shrewdly held their annual retreat in the new facility – the very first campus event.) The rector did note, however, that classes on the first day were very short: “There being no books and no desks, very little was possible.” But the school was launched and Bishop Ireland was not finished building.

An important opportunity to continue what he had begun came quickly and took almost everyone by surprise. James J. Hill, the railroad builder, announced in 1890 that he was donating $500,000 (a magnificent sum at the time in Minnesota) to fund the construction of a graduate seminary for the diocese. Inspired by his Catholic wife, he was convinced that the education of priests along the lines that Ireland endorsed would be a profound benefit to the community. In 1894 the St. Paul Seminary was finally ready for occupancy and that fall, when the seminarians moved across the street (to what is now the university’s south campus), the College of St. Thomas came to life as a separate institution.

Ireland’s continuing devotion to the college had been evident in January of that year, at which time he gave to the board a deed to the land. This land was Ireland’s personal property, not the property of the diocese, and so it was perhaps not unusual that he attached three conditions to the gift. First, the property was to be used for Catholic higher education for young men in Minnesota and the upper Midwest. Second, in keeping with his devotion to the local Church, the college was never to come under the control of a religious order. Third, and most striking, in the event that these two conditions could not be honored, the property would “pass over” to the Sisters of St. Joseph (the community governed by Ireland’s own younger sister) for the Catholic education of young women. (When, a decade later, the College of St. Catherine opened, Ireland was a sponsor and a frequent visitor.)

What should we make of John Ireland, a century after his death? Today we might call him an entrepreneur and an optimist, as indeed he was. He was also a keen observer of his time, whose restless imagination was powerfully attracted by new ideas and excited by new problems to solve.

He believed that, to speak to the modern age, it was necessary for the Church, and for individual Catholics, to embrace their intellectual tradition and to pursue education passionately. A good deal of his energy was directed to this project and he was not easily deterred.

Over the last two decades of the 19th century, and the first of the 20th, he played a major role in the foundation of four institutions of higher education (including the Catholic University of America and the College of St. Catherine) that thrive today, but none was more important to him than St. Thomas. John Ireland would be pleased to know that his vision of faith and community engagement continues to inspire the university he founded.