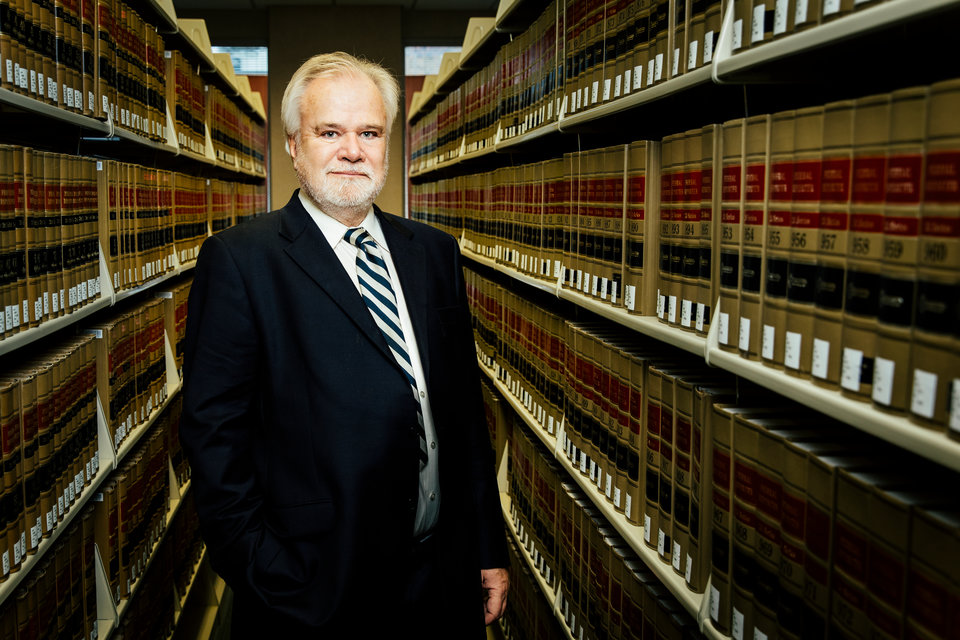

Professor Robert Delahunty’s career as an academic tracks a history of success that spans two continents, four decades and some of the most prestigious institutions in the English-speaking world. Before coming to the University of St. Thomas as one of the school’s resident experts on constitutional law, he taught as a tenured lecturer in classical philosophy in Oxford and Durham, England, before taking his law degree at Harvard and serving as counsel in both the U.S. Department of Justice and the Office of Homeland Security.

As a scholar, Delahunty’s writings are as broad and diverse as his professional life, having written on topics ranging from the international law of war to immigration, constitutional originalism, Shakespeare, Descartes and Spinoza. Recently generating interest after the fallout of the November election with his work on the laws governing the Electoral College, on which he lectured at his investiture of the Laurence and Jean LeJeune Distinguished Chair last spring, his interest in topical subjects as well as academic ones is just as diverse. As a regular contributor to the National Review and blogs like the Federalist and St. John’s Center for Law and Religion Forum, his work is just as accessible online as it is in a more scholarly journal.

More recently, his piece discussing the possibility of a Concert in Asia (a group of countries forming an alliance), viewed through the historical lens of the 19th century post-Napoleonic Concert of Europe, is slated to be featured in a forthcoming edition of the University of Pennsylvania’s East Asian Law Review.

But despite his work and accomplishments as an attorney, lecturer, writer and scholar, Delahunty’s primary contribution to the life of the University of St. Thomas is of a rather different character. Having been trained and tutored in the Oxford way before he would became a tutor at Oxford himself, it was those formative years that taught him to be more than just a scholar, but a teacher and mentor, as well. Although an American and, to some extent, an outsider to the life and culture at Oxford, his own teachers and colleagues there taught him what it truly means to teach.

The life of a scholar, and indeed any true thinker, is not something that can be transmitted purely in the abstract – relying only on lectures, tests and assignments – but is much more holistic in nature. It is a life lived in a community of like-minded individuals who share a similar goal or pursuit, and develop their proficiency with a subject as part of a learned whole. The relationships formed, just as much as the ideas themselves, were responsible for the intellectual, and ultimately personal, development of all involved.

Delahunty exemplifies this in the same way he was taught at Oxford. With generosity to match academic rigor and hospitality to match scholarly nuance, he seeks to honor the legacies of those men whom he admired and who taught him so much during his time as a student. “I recall with special fondness the older fellows,” he said, “who treated their young American colleague with immeasurable kindness. These were like fathers to me. Several were veterans of the Second World War, and had fought in the Battle of Britain or in France or Crete. Some were refugees from Hitler. They were learned, witty, traveled, urbane and intensely civilized. They were old-fashioned English gentlemen. I might join them on a Saturday morning to read Sophocles aloud together in Greek, or Racine in French. And they cared for their students as close friends.”

These experiences inform his role at the law school today, and the teachers he knew and was mentored by have become models for his own teaching style. Opening his own home countless times throughout the year to host students for dinner, school-related events or simple social gatherings, he has, in his own way, brought the flavor and environment of one of the most renowned universities in the world to the University of St. Thomas. These social and relational elements turn education into formation – formation not just of the mind, intellect or capacity to study, but of the whole person.

Culture as much as classroom hours are central to developing individuals who can think, reason and ultimately live out their careers as more complete men and women who are more able to meet the needs of those they encounter. Education unmoored from virtue, magnanimity and kindness becomes stale, rote learning devoid of any humanity. But when character is formed along with the mind, and is imparted with the grace and generosity that comes from a shared and mutual conviviality with one’s peers, the learning takes on a refinement in which it becomes about more than itself, but about the people with whom one shares it. Though valuable for its own sake, knowledge does not have such stringent limits, and it is just as desirable for the sake of others as well.

For Delahunty, this is a principle to live by. The students of the law school, even more so than the study, honors and scholarship, are at the heart of his role as teacher. And it is in such a way that a professor who teaches law can become a mentor who raises up fully formed men and women to be nothing less than what the Gospel enjoins us all to be: the light of the world and the salt of the earth.

Read more from St. Thomas Lawyer.