Doodling. Widely considered the work of distracted minds, it's never had the best of reputations. And while it may not take the top spot on a college professor's list of student-related laments, many will admit to poo-pooing its presence in the classroom. The Oxford English Dictionary even defines doodling thus: "to draw or scrawl aimlessly."

Despite doodling's bad rap through the ages, in recent years it has taken a turn in acceptability for its ostensible ability to aid in cognitive performance from memory recall to creativity to concentration. England has a national doodle day, as does the United States (May 9). Google has had a chief doodler on staff for nearly 15 years. And proponents of doodling are quick to cite famous doodlers who were/are successful in their fields, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sylvia Plath, Hillary Clinton and Bill Gates.

In a widely publicized 2009 study, doodling was found to significantly enhance memory retention. Jackie Andrade, a professor at the University of Plymouth in England, found that doodlers retained 29 percent more information than nondoodlers. She noted that, contrary to popular belief, doodling seems to prevent people from losing focus on boring or complex subject matter, and that it keeps them from daydreaming by providing an "attentional anchor."

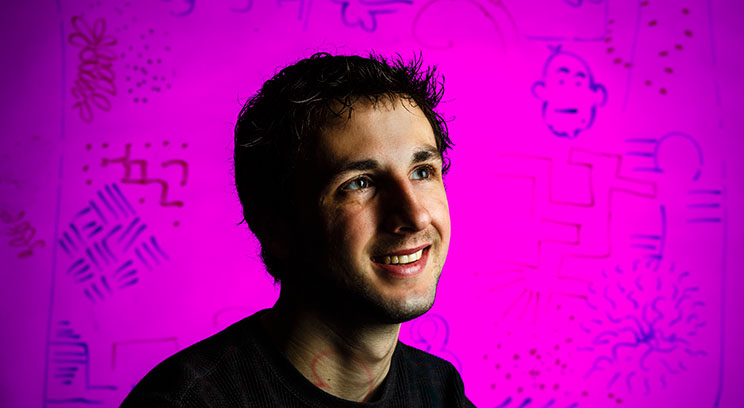

But the results of St. Thomas senior Scott Fusco's study may deflate some of the pro-doodling excitement. Fusco, a psychology major, was interested in delving into doodling "because it's a common thing people do whether they realize it or not, especially in classroom settings." His findings, however, “were in direct contrast to the original study done in 2009."

"Surprisingly, no one had replicated Andrade's study," Fusco said. "My adviser (Dr. Greg Robinson-Reigler) and I wanted to replicate it because in the sciences it’s important to replicate studies to see if results are consistent and attributable to the independent variable (or what is being manipulated), rather than due to a flaw in the study or some other factor."

So last semester Fusco rounded up 30 St. Thomas students, ages 18 to 22 (Andrade's study, which was published in the journal Applied Cognitive Psychology, looked at 40 participants, ages 18 to 55) and had them listen individually to a rambling, two-and-a-half-minute-long mock voice mail recording in which the speaker extends a surprise-party invitation and write down the names of the people going to the party. But it's not so simple. During the message, the caller veers in every direction, from kitchen remodeling to a camping disaster in Duluth to the ingredients of a punch recipe, all of it peppered with interjections of who will be in attendance, who won't and why or why not. Your basic nightmare.

Half of the group were given a sheet of paper containing columns of shapes – 100 circles and squares in all – to fill in while they listened to the recording; the other half simply listened. Fusco then instructed each participant to recall the names of the attendees they had just written down. Before listening to the taped message both groups took two tests that measured their working memory capacity and how well they could multitask.

The results don't seem noteworthy at first glance: The doodlers scored 6.86 out of a possible eight (of the targeted attendees' names) correct, while the nondoodlers answered 7.13 correctly on average; however, "That's the key finding right there," Fusco said. "That small percentage difference is considered statistically significant."

What might account for the opposing studies? Fusco said he can only theorize: "I think my participants may have been subject to dual-task interference (when people have difficulty performing two seemingly simple tasks at once, their attention and performance become impaired), which has been commonly found by researchers among people. Andrade's participants did not seem to experience any such interference, which is very intriguing, and I am not sure why. Any number of factors could have played a role in revealing this interference in my participants, such as level of boredom, mood states and maybe even performing the working memory and multitasking tasks before listening to the taped message. Maybe performing these two tasks beforehand enhanced more executive resources thus opening up more avenues for distractions?"

Admittedly not a doodler himself, Fusco believes running for St. Thomas' cross-country team helps him stay focused and alert during lectures. He does, however, have some advice for chronic doodlers: "Limit the amount of things you're doing in class, and put things down in your own words versus copying verbatim what the professor says – it'll help your executive functioning." He added that, "People should be consciously aware of when they are doodling or even bored rather than drifting off into space and daydreaming. Just being aware can help negate or lessen many of the possible negative consequences that may result from doodling/boredom, etc."