On April 12, 2015, Pope Francis officially proclaimed St. Gregory of Narek a Doctor of the Church, bringing the number of saints honored with this title to thirty-six. Those recognized as Doctors of the Church must meet three criteria: (1) eminens doctrina, “eminent learning, outstanding scholarly achievement” that is of great advantage to the Church, (2) insignis vitae sanctitas, “a high degree of sanctity” that is exemplary for all Christians, and (3) ecclesiae declaratio, “proclamation by the church.” Enrolled in this august group are some of the holiest saints and profoundest theologians the Church as has ever produced, such as Sts. Athanasius, Augustine, Bernard of Clairvaux, Thomas Aquinas, Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Ávila, and Thérèse of Lisieux. Given that St. Gregory of Narek is virtually unknown among Roman Catholics, the choice by Pope Francis to name him a Doctor of the Church came as a surprise. The choice, nonetheless, is not without significance.

On April 12, 2015, Pope Francis officially proclaimed St. Gregory of Narek a Doctor of the Church, bringing the number of saints honored with this title to thirty-six. Those recognized as Doctors of the Church must meet three criteria: (1) eminens doctrina, “eminent learning, outstanding scholarly achievement” that is of great advantage to the Church, (2) insignis vitae sanctitas, “a high degree of sanctity” that is exemplary for all Christians, and (3) ecclesiae declaratio, “proclamation by the church.” Enrolled in this august group are some of the holiest saints and profoundest theologians the Church as has ever produced, such as Sts. Athanasius, Augustine, Bernard of Clairvaux, Thomas Aquinas, Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Ávila, and Thérèse of Lisieux. Given that St. Gregory of Narek is virtually unknown among Roman Catholics, the choice by Pope Francis to name him a Doctor of the Church came as a surprise. The choice, nonetheless, is not without significance.

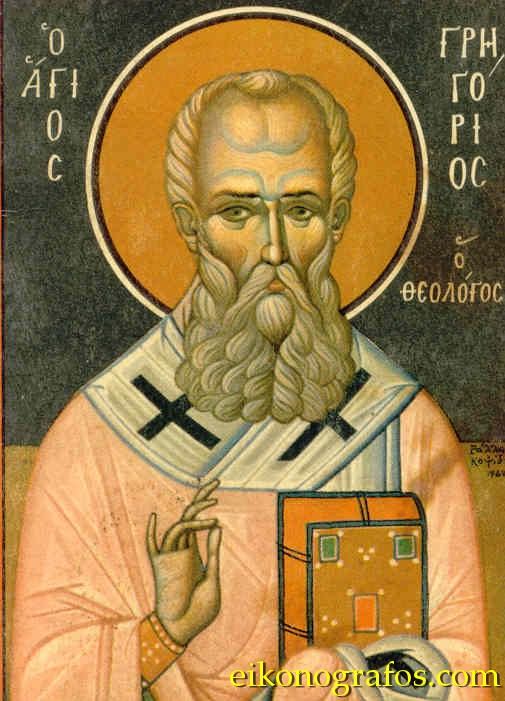

St. Gregory of Narek lived and died as a member of Armenian Apostolic Church, making him the only Doctor who was not in communion with the Catholic Church during his lifetime. To the present day, the Armenian Church preserves a very ancient tradition of Christianity. Armenia was the first nation to adopt Christianity officially, traditionally in 301, years before Constantine converted to Christianity and initiated the Christianization of the Roman Empire. In that year, St. Gregory the Illuminator, a Greek-speaking Christian from Cappadocia, healed King Trdat (Tiridates) of Armenia of a mental illness, prompting his conversion. Through the efforts of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the Christian faith spread rapidly throughout Armenia and became deeply embedded within Armenian culture. In the early fifth century, an alphabet was created to write the Armenian language, and soon thereafter the Bible was translated into Armenian, leading to a literary, cultural, and religious renaissance in Armenia. In the aftermath of the Council of Constantinople in 553, however, the Armenian Church severed its ties with the Latin- and Greek-speaking churches over Christological differences, becoming most closely aligned with the Syriac and Coptic Orthodox Churches. As in many Christian traditions prior to modern times, in Armenian Christianity, monasticism was seen as a fundamental expression of the Christian life. Hundreds of vibrant monasteries were founded. Unlike western monasteries, which tended to be isolated from lay persons and political centers, Armenian monasteries were deeply integrated in the ordinary lives of lay Christians, and monks were seen by kings as trusted advisors and confidants. Monasteries were also centers of Christian learning and education. Kings often sent their sons to monasteries to be educated. The chief scholars were known as vardapets, Armenian for “church teachers.” One such vardapet was St. Gregory of Narek.

St. Gregory was born somewhere between 940 and 951 in the Armenian town of Andzevatsik, which is located in modern-day Turkey. At an early age, he entered the monastery in the village of Narek on the south shore of Lake Van, which is also located in modern-day Turkey, and remained a monk there until his death in 1003. Gregory lived during a time of peace and prosperity, which enabled him to live the monastic life in all its rigor and devote himself to spiritual writings. His earliest extant writing is a commentary on the biblical book the Song of Songs in 977, which is notable for its ample use of earlier Greek commentators on the biblical book, particularly Gregory of Nyssa. Though St. Gregory of Narek is the author of many works, his fame rests upon the Book of Lamentations, a collection of ninety-five prayers he completed shortly before his death. Here his talents as poet, mystic, and theologian are most fully on display. His poetry is deeply biblical and suffused with the images, themes, figures, and events of salvation history, while at the same time being intensely personal. In form, his theology is not an intellectual reflection upon God, but rather a dialogue with God in prayer, “speaking with God from the depths of the heart.” According to Gregory, the goal in life is to reach God, to achieve union with God (insofar as human nature allows), to erase the differences between God and humans. This union cannot take place at the level of the intellect, but only at the level of the heart and feelings through experience of God.

Cardinal Angelo Amato, the Prefect for the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, pointed to four areas of special distinction in the doctrine of St. Gregory of Narek which contributed to his being named a Doctor of the Church: (1) his realistic appreciation for the gravity of sin, which limits human beings and makes them incapable of speaking with God without the mediation of the incarnate Word; (2) his profound dogmatic reflections on the mystery of the holy Trinity; (3) his defense of the sacraments as efficacious mediations of divine grace in the Church; and (4) his devotion to Mary, particularly in her role as mediator between God and humanity.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in St. Gregory among Roman Catholics. Pope St. John Paul II laid the groundwork for this. He mentioned St. Gregory, with approval, in several speeches, in the 1987 encyclical Redemptoris Mater (Mother of the Redeemer), and in the 2001 Apostolic Letter to the Armenian church. The Armenian saint is also mentioned in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (Art. 2678), where his hymns to Mary are praised. In 1996, John Paul II and Armenian Apostolic Catholicos Karekin I issued a common declaration of faith in Christ, in which they agreed that they believe the same things about Christ, even if they express these things in different language—language which in the past unfortunately led to divisions between Catholics and Armenians in the aftermath of the Second Council of Constantinople in 553. Thus, this statement effectively exonerates St. Gregory of any “Christological” errors: even if St. Gregory was not in communion with the Catholic Church, in doctrinal matters there was complete agreement.

When Pope Francis officially proclaimed St. Gregory of Narek a Doctor of the Church on April 12, 2015, it is surely no coincidence that it was at a mass he celebrated with members of the Armenian community in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the start of the Armenian Genocide, which is held to have begun on April 24, 1915. The crumbling Ottoman Empire’s involvement in World War I had brought it to the verge of collapse; after the war it would be dissolved and reorganized into the modern-day Republic of Turkey. The last years of the Ottoman Empire, from the 1890s onward, were accompanied by the rise of a virulent form of Turkish nationalism. The Ottomans wanted to purge their empire of all non-Turks, including Armenians who, for millennia, had lived in what is now eastern Turkey. Armenian lives were thus suddenly imperiled in what was their homeland. Many Armenians were expelled from Ottoman lands, but as many or more were exterminated; scholars estimate that between 1 and 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman government through 1923. The Armenian Genocide is considered the first modern genocide; in fact, the word “genocide” was coined in the early 1940s by Raphael Lemkin to describe the massacre of the Armenians. Today’s Republic of Turkey has continued to refuse to acknowledge that its predecessor state, the Ottoman Empire, was responsible for the Armenian Genocide. Armenians want Turkey to admit the Genocide, not only because it is the truth, but also because admission is necessary for justice. It would also be the first step for reparations. Armenians suffered tremendous losses of life, property, and cultural heritage. For example, the monastery where St. Gregory of Narek lived had remained active until 1915 when it was abandoned. It was destroyed by the Turks in the 1950s, and a mosque was built on its site. So by naming St. Gregory of Narek a Doctor of the Church, Pope Francis is not only recommending the writings and exemplary life of a great poet and theologian for our intellectual and spiritual enrichment, but also showing the solidarity of the Roman Catholic Church with the Armenian Church—a very powerful statement in the face of those who continue to deny the Armenian Genocide.

Mark Del Cogliano is an assistant professor of historical theology at the University of St. Thomas. He has been on faculty since 2014.

From “theology matters,” a newsletter of the Department of Theology. Subscribe here.